This could be another tale of pottery on a shoestring. Even in Switzerland, the fabled land of milk

and money. There's plenty of both seemingly, its

just that the latter is harder to come by. You

either have it or you don't. If you don't then the

prospect of constructing a large kiln in a foreign

country could possibly be a daunting if not impossible exercise. However, after two and a half years

of travelling and working in Europe, being totally

unconcerned about clay and pots and kilns and firings, it came to a point where naturally I had to

pick up the potting reins again. Pick them up certainly, but only on an all or nothing basis. The all

being the kind of working and living situation with

the kiln I'd always dreamed about since dicovering

clay for the first time. The nothing being a permanent change of direction, away from pots. From

the heart, the second option could never have

happened out of circumstances it could well have

come to pass. When making criteria eventually

dictate only one direction, in this case working a

very large anagama buried deep in the ground, it

is easy to see that the options are limited. Even

so when one owns not his own walls (which have

to be in the right place for such purposes), or his

own land, or has access to anything more than

minimal financial resources.

A big wood kiln requires a permanent space, it

is not something you can easily take on holiday. It

also needs enough room for at least a years wood

supply, with planning permission usually a burdensome necessity. The man is therefore limited to

owning his own property, with land, somewhere well

out of town. This either calls for rich relatives or

several Hans Copers to sell. The only other alternative is walking a tightrope by relying on the

unceasing good will of a landowner, and finding someone suitable to put up with such a ridiculous

escapade is not an easy task. To get all these prerequisites on one plate is an almost impossible

occurence. Even if it does become reality, there is

then the problem of obtaining firebrick, and that

is invariably a very expensive commodity.

Fortunately, my affair with making pots

has always been concerned with the roots. Those

simple beginnings and fundamentals of the pot

making process that have seemingly and virtually

disapeared as a direct result of modern trend. Roots

speak of simplicity. Simplicity rarely costs a lot,

especially when mother luck trots merrily alongside.

There are a few potters interested in real fire, even

fewer who really understand it, the majority preferring the lure and folly of techno innovation and

contemporary modality. Thus objects are constantly

produced from clay that may well be technically and

intellectually brilliant but sadly lack little heartfelt

aesthetic or loyalty to the origins of the craft.

As a result, my pot making development has

been inextricably bound up with kiln development.

Not in a technological manner, but in a way that

I can only describe as something that results from

a primaeval instinct and well considered perception.

I envy that caveman for his feelings when he first

discovered that fire bakes clay. Imagine the elation.

I think I touch on it when I am firing. I certainly

feel like jumping around and making unintelligible

grunts. Its borne out of a feeling of understanding

yet at the same time not understanding of being

in awe. The more I strive to capture the process

of nature in the way I make and fire, the closer

I get to the roots.

The kiln that now stands on a previously usable

patch of Emmental dairy farming land, realises the

dream of a decade. Its conception and construction

born out of a mixture of pure good fortune and

plain hard graft. The beginnings of it all originate

with a much used and abused hole in the ground at

Farnham ten years ago, a period still close to my

heart and already written about at length in Pottery

Quarterly Vol. 14 No 54. It was at a time when I

had pottery heroes. Their early influences gradually

Imellowed over the years to a point where I can

say my only influence now comes from my materials

my kiln, pots from previous firing, and sometimes,

though goodness knows why, the perpetual and

melancholic clonk of Swiss cow bells. I still have

the heroes, though most of them have passed on.

The legacy of Hamada, Leach and Cardew, and

treasured memories of those I knew such as Paul

Barron and Henry Hammond, these alone are

enough encouragement for me to retain a dogged

allegiance to traditional methods.

So it was in autumn of 1988 that I happened to be

present in the middle of a field with a Swiss farmer

who I'd never even met before, confronted with the

possibility of achieving the almost impossible. He

waved one hand haphazardly at the rising slope

before us, said I could build here somewhere, and

went back to milking his cows. There I stood,

surrounded by rolling hills, pine forests and laidback

Swiss farmsteds with my knees quaking in utter disbelief, as though I'd suddenly got the whole world

in my hands. The ten year dream was about to

become reality, I'd experienced the elation of that

caveman, and I was searching for a shovel.

The Mule is a blend of well proven principles.

The donkey and the horse both have their attributes

but the mule, a beast of draught and burden has all

of them put together. It is of course undeservedly

noted for being stubborn, but probably only as a

result of being mistreated by its owner. Thus like

all my previous kilns, this one was also given a

name, and as a conglomeration of ideas I'd been

working on since Farnham, The Mule fitted well.

Its predecessor, Bacchus, was a prototype, a

pseudo anagama (if there exists such a thing) from

which I learnt even more about firing technique and

kiln behaviour.

My previous workshop, a disused farm on the

outskirts of Northampton, was a bleak place at the

best of times, but as a pottery and a place for

firing it served its purpose well. I lived and worked

next to Bacchus in disused pig sheds for eighteen

months and became labelled eccentric by the press

because of it. However, since that first hole in the

ground at Farnham, I've only ever been interested

in wood fired single chamber cross draught kilns.

A case of choosing the ride and sticking with it.

If you die by the side of the road in the process

so be it, but the choice is one of a devotee and an

inbuilt mania to see it through. The cross draught

wood kiln boasts two main characteristics not so

inherent in other kilns. Firstly, dependent on the

length, there is a decreasing temperature gradient

from firebox to flue, and secondly, like it or not

virtually all the pots end up with a front and back

irrespective of how they were made. The latter is

unavoidable, as a direct result of flame and ash on

one side and the flue on the other. I still don't like

to see my pots the wrong way round however subtle

or beautiful their backs are. I periodically go

through the house turning them round after unknowing visitors look at them and put them down

back to front.

The former characteristic of decreasing temperature gradient I gave a lot of consideration. Up to

a point you can go with the flow and place lower

firing glazes at the back. An admirable solution and

to work with rather than against that flow is very

true to the natural processes on tap. However, I

found myself relying more and more on the same

vitreous slip and high firing shinos, and less on

lower firing ash glazes. A side stoke half way up

would be the obvious answer, or several, dependent

on the length of the chamber. Principles used by

our ancestors for centuries, of course. Nevertheless

the inherent problem with the climbing cross-draught kiln is that the chimney naturally tends to

suck the heat out of the back part of the kiln

faster than its being fed in at the front. Close the

damper to counteract that and the kiln reduces and

fails to gain any further temperature rise. Evidently

necessary was some sort of back pressure.

In designing Bacchus the rest was relatively

easy. A Bourry firebox was a foregone conclusion

as i know it well. If it is built sufficiently large it

will fire anything to whatever temperature you want

with no fuss, providing of course the hole the other

end of the kiln is big enough too. I wanted the

floor of the chamber higher than the top of the

firebox to induce positive pressure and I wanted the

floor of the chamber to rise towards the flue. So

I really needed a hillside but I had none. Just an

empty pig shed. Not to be outdone, I built the

equivalent of a hillside out of concrete blocks and

rubble and perched the chamber on top of that

instead. This would have left the base of the

chimney three feet above ground level with only

five before it exited the pig shed. Flames out of

the stack can be great fun especially at night with

a camera, but also have a habit of creating an

unecessary and disturbing commotion that any potter

in his right mind would do well to avoid. How to

get the back pressure I required with a long enough

chimney in so little space? The answer was, as

usual, a logical one. I built a double skinned

chimney that incorporated a 'flue' from kiln floor

to ground level and then back upwards again as a

chimney. This configuration gave an extra eight feet

of flame flow and wonderful back pressure, decreasing the temperature gradient within the chamber

by about fifty degrees. Thus side stoking to raise

the rear part of the kiln to the required temperature became a relatively short and trouble free

exercise. In building the stepped floor, I hit upon

the idea of stepping the arch too, so the height of

the chamber at the back was the same as at the

front. Being free standing with sprung arches, the

whole structure required a fair amount of ironwork,

something well within the capabilities of a hacksaw

and home welder. Ironwork to my mind however,

does not look right. It's just not sympathetic.

Bacchus, at about eighty cubic feet, was simply

not big enough. The most important thing was, that

as a major experiment it worked, and worked well

it did. It was capable of reaching 1300oC in fifteen

hours, but I always used to fire for about thirty six,

and twelve of those at top temperature. I also required precious little wood. I built it, fired several

times for nothing using demolition timber and then

pulled it down. Burning my bridges I left dear old

England with a dream of transposing Bacchus into

a real anagama sunk into the ground. At least twice

as big, with a chamber like half an egg, completely

self supporting, and fired for much, much longer.

Where, when and more importantly with what means

gave me moderate cause for concern.

South in the Valais, nudging the Alps is a giant

aluminium smelting works. Twice a year they have

to reline the furnaces, and the resultant rubble is

deposited in the forest. The biggest firebrick tip you

ever did see. It took six days of digging them out

sorting and then stacking on pallets before I had

enough. Fifteen tons of grubby, well blasted, but

high quality bricks, and I was black from head to

toe covered in a not too healthy mixture of sweat

and aluminium dust. While sitting in the sun on a

campsite, a rather drunk but accommodating Italian

lorry driver was bribed into delivering them for me.

The bricks worked out at £5 a ton, the lorry four

times as much, but, I was well pleased.

Planning permission for the Mule took three and

a half months. It went to five different Swiss

offices. Some Cantons do not even allow wood kilns

- a strange conception since most country dwellings

are heated with wood stoves all the year round.

I managed to get the shed up before the first snowfall, The farmer donated tree trunks for the main

supports and the rest was built from machinery

packing cases. I paid only for the roofing sheets,

and reluctantly at that. The first snow as good

as buried the whole lot, but inside I was happily

digging the hole.

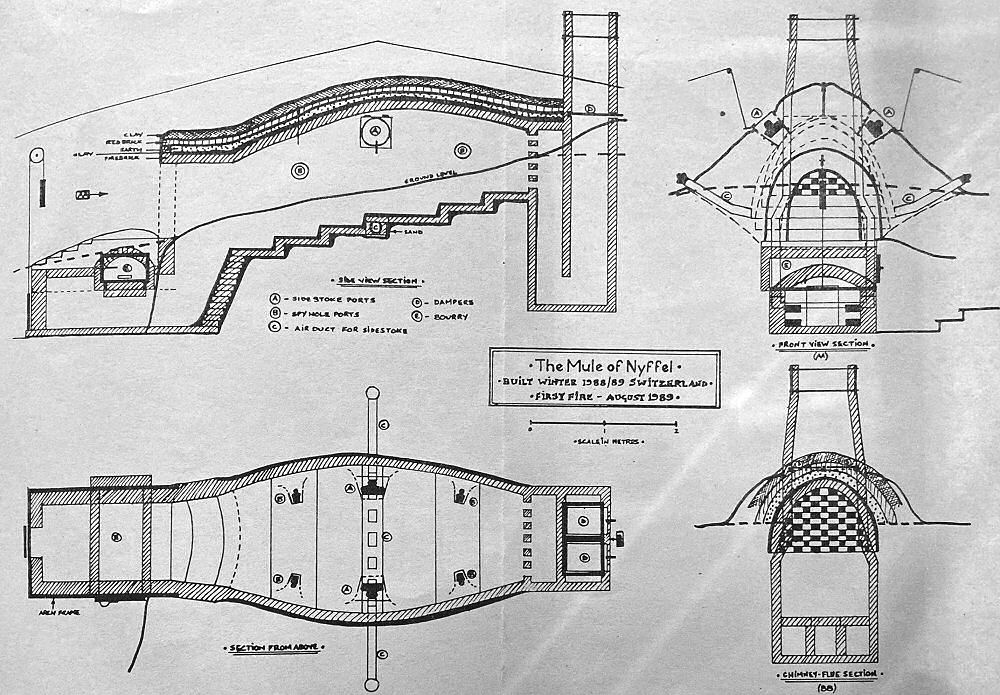

The transition from inches to centimetres posed

head problems at the outset, but I was in mainland

Europe and metric is more logical. Thus the Mule

was designed and constructed using a metre rule.

I do not build using any fixed parameters from

other sources. I use a little experience (this is the

eighth I've built) mingled with some common sense

and instinct. I certainly fire by instinct. Not many

people have it, maybe I'm lucky. There is such an

unaccountable myth associated with wood firing and

and a most absurd ineptitude to go with it. Lack

of instinct answers a lot, and so does lack of

gumption. Instinct is about feeling, conscious or

unconscious, and gumption is plain initiative. Can

you remember the last time you actually felt a

a gentle breeze on your face? Feeling the state

of a wood kiln during firing is not that different.

It is just a case of being aware. Designing and

building a wood kiln that functions well is simply

a logical understanding of the principles of combustion. Critical areas such as throat arch, bagwall

space, flue exit and chimney section should not be

built too tight. It's much better to be over generous

in these parts than to have a major problem later.

For instance an over large chimney section can be

controlled with dampers, if it is too small it has

to be rebuilt. The firebox volume in relation to

chamber volume is also important. It must be big

enough. The firebox of the Mule was designed

specifically for easy firing, high temperature and

a good ash deposit. The ashpit floor is half the

length of the chamber. The chamber floor rises in

six steps with a duct half way up to provide air for

side stoking. This air duct reaches the outside world

through clay drainage pipes on both sides of the kiln

and is an absolute must for efficent combustion in

this part of the chamber.

I found myself digging into a seam of gravel a

metre down, which with a finishing bed of sand,

provided a solid enough base for the floors and

foundations, and good drainage as well no doubt.

Digging the deep hole for the chimney was therefore

a trifle tiresome, but the advantage of having most

of it underground is that only a metre and a half

from a total of six protrudes above ground level.

This is of course environmentally friendly in terms

of landscape and possibly impressive in the planning

office, though which one I couldn't say.

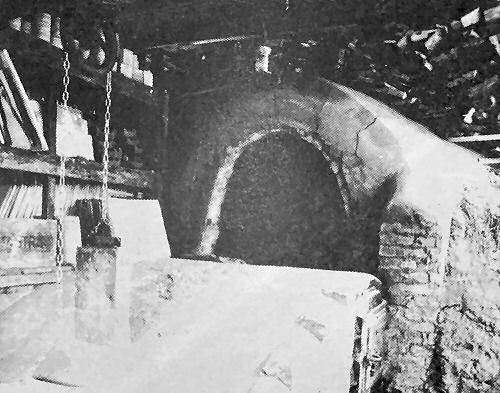

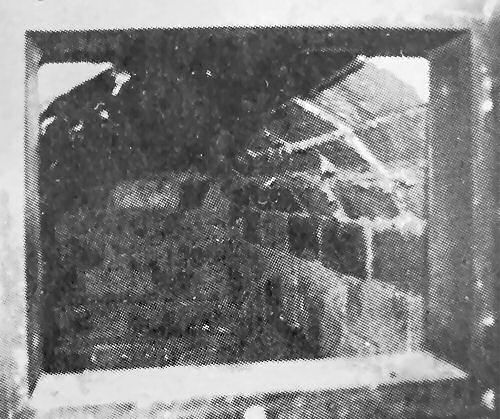

The Mule was built in the order of firebox, kiln

floor, chimney and flue together and finally the

chamber. Finding scrap in Switzerland is not easy.

I might just as well have been looking for a needle

in a haystack. Nonetheless, I eventually secured all

those little extras I needed. The firebox was braced

with an iron frame to support the arches, and an

old but elegant cast iron bread oven door (with a

primary air slot no less) was given a new lease of

life as a Bourry firebox.door. I had always wanted

an ashpit with a door on a chain and pulley

balanced by a counterweight but previously I had never got around to it

This time I did. It works magnificently. Gary Wood, an ex-student of Mike

Dodd remarked that it was the only kiln he had

come across with a self flushing firebox. I fact the

whole firebox works so well he could be right.

Note should be made here regarding throat arch,

bagwall and bagwall space. I have come across many

kilns that have been built with the bagwall space

far too tight and almost without exception their

owners complain of the age old problem, getting

to temperature. Whatever the cause this can always

be answered without having to look far. There is

no myth. The throat arch is subject to the highest

temperatures in the kiln, and if the bagwall space

is too tight this leads to a wonderfully hot firebox

but a miserably cold chamber. Flame has a volume

and requires a certain amount of space to move,

if restricted in the bagwall area it will not heat the

chamber. Bacchus may look a little tight in this

point, but for the chamber size the bag wall was

just sufficient. For the mule with a 2.25 increase

in volume I enlarged the bagwall space comparatively. The bagwall equivalent is not only concave but

is inclined away from the firebox, i.e. the bagwall

space increases as it becomes chamber space. This

is both constructional and theoretical. Such a wall,

if built vertically and straight, will after several

firings bow towards the firebox simply because it

gets so hot. This naturally results in reduced bagwall space and irksome repair work. Flame volume

increases up to a point the further away from the

firebox it gets and then proportionately decreases

towards the chimney exit. The increasing bagwall

space permits easier combustion and the inclining

'bagwall' is sympathetic to the flamepath which by

its nature dislikes corners.

| Relative Proportions (cm.) | Bacchus | Mule |

| Packing space | 2.2m3 | 5m3 |

| Ashpit length | 148 | 215 |

| Chamber length | 283 | 400 |

| Max chamber width | 110 | 200 |

| Max chamber height | 90 | 140 |

| Firebox floor to chimney top | 290 | 440 |

| Bourry firebox length | 110 | 140 |

| Bagwall height | 75 | 104 |

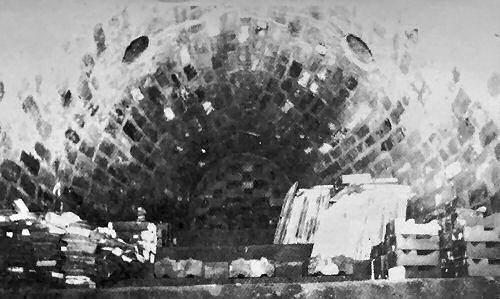

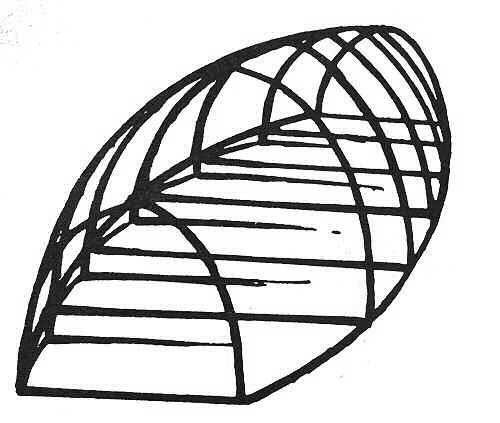

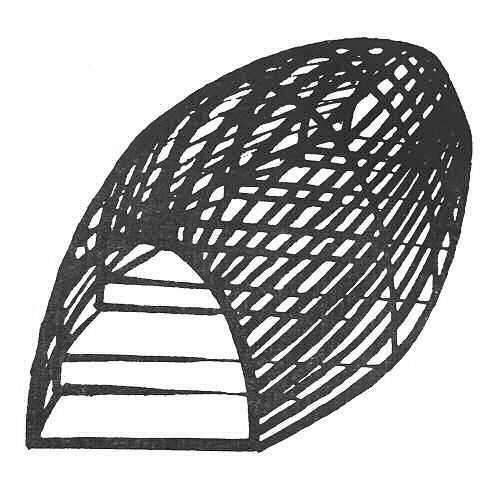

I think the most enjoyable part of the whole exercise was building the

chamber. Everything else was finished, firebox, chimney, floor, flues

all it needed was the 'top'. With one long baton sprung from end to

end in a shallow arch I could visualize height to width proportions

and the height of the arch at any given point from front to back. I

then calculated, drew out and built seven U section formers from scrap

timber (fridge packing cases to be precise). With two of these positioned

at either end and the remaining five, one on the front of each step,

I could then form the main shape by pinning roofing batons over the

whole lot. It looked beautiful, just like an upturned

boat in its early stages of construction. It seemed a shame really to

cover it first in plastic, and then bit by bit with a single skin of

well laid firebrick. Half way up, on both sides, I set in two spy hole

ports and a side stoke port. these were made as conical cylinders, thrown

out of firebrick clay and and fired in a test kiln that I had also built

from scrap. Building the chamber took only two days, but after laying

bricks for weeks in sub zero temperatures knocking in the final one

was a relief. I can clearly remember impatiently burying the entire

construction under a great mound of earth and diving into the chamber

with a hammer to knock out the former. (Being buried the arch becomes

self supporting). After all the timber and rubble was thrown out of

the entrance I sat up the far end looking down and out of this great

oval dome, with its six round skylights, shaking with some kind of primitive

bewilderment, almost disbelief, at the beauty of it all. To think that

all this would soon be white hot hardly bore thinking about. It was

a long time before I came out again.

The finished arch was covered in a thick layer of high temperature clay

mixed with sand and sawdust. At a later date, the very obliging farmer

rebuilt his cowshed, and presented me with a trailer load of old and

very smelly red bricks. A layer of these was finished off with another

layer of clay dug from the nearby forest, again mixed with sand and

sawdust by foot. The chamber was now nearly half a metre thick at its

thinest point and well insulated. I threw side stoke and spy hole bungs

from firebrick clay, and made a pair of quick action iron doors rigged

up on pulley wheels for easy stoking. A little bit of luxury. The kiln

floor and bagwall were finished off with a mixture of 90% grog and and

10% clay. A bit more landscaping and it was finished.

The mule took four months to build and was constructed entirely from

scrap and recycled or found for nothing materials. It cost the equivalent

of £1000 including all transport and all kiln furniture. I collected

150 large silicon carbide kiln shelves and and 220 solid silicon carbide

props from the back door of the local porcelain factory. Second hand

of course and destined for the scrap heap, but it's amazing what you

can still get for a crate of beer. Conversely I might mention that I

heard of a 12 cu ft. gas kiln that cost the equivalent of £5000.

Later I came across a computerised electric kiln without a spyhole of

any sort. Ye gods, what is happening, I thought to myself! How can anyone

consider firing any kiln without being able to look inside it? It was

then that I realised how long the arm of decay has become. Real Pottery

could be called Real Kilns, Real Farming or Real Anything Else come

to that.

Most Swiss country houses are made of wood and the ones that get pulled

down to make way for more concrete provide a rich source of well seasoned

pine for firing. The Swiss have little interest in demolition timber,

its full of nails and difficult to stack neatly. For me its ideal and

usually free. Wood from the gradually dying forests is not really suitable,

it costs money and I have to keep it for at least a year before its

dry enough to use. I am now firing for two to two and a half days. It

gets longer every time. The lengthening of the firing cycle happening

because I rely more and more on the fire to decorate. The longer the

better. My making and decorating techniques have become very simple.

I use only one or two Shino glazes, but mostly just a vitreous slip,

nepheline syenite based. Sometimes nothing at all. Just clay. Just like

that caveman. The critical factor with such a long firing is of course

physical limitation. To fire for three days for instance requires a

certain amount of conditioning which can only happen over a long period

of time. I can never leave a firing even for a few hours in the hands

of someone else. On the few occasions I ever have done they've always

proved to be disasters, one way or another.

For firing and packing techniques refer to Pottery

Quarterly Vol. 14 No. 54. An approximate outline of my current firing

cycle is as follows:-

The first twelve hours - gradually to 400oC.

400oC to

The twelfth to the thirty sixth hour - 1300oC

pausing for an hours clean burning at 850oC, followed by

deliberate heavy reduction for the body from 920oC to 1000oC

over two hours.

Thirty sixth to the forty eighth hour or more - natural

cycle of oxidation and reduction brought about by stoking, the same

as for 1000oC to 1300oC. During this time temperature

rises to between 1300oC and 1350oC. Final two

hours clean burning followed by fast cool over one hour to 1000oC.

One may be tempted to ask why? To fill it takes about two and a half

months work, which means I only fire about three or four times a year.

The learning is inevitably slow with such a long period between one

firing and the next. Economically, both in terms of time and fuel it

works. It is clearly a long term project. With each firing comes a little

more understanding. The marriage of materials and flame together with

draught being a constant source of investigation. I don't think I could

work with anything less now a big kiln, holy fire and buzzards circling

overhead. Oh yes, that is the romantic side of it all the reality is

a kamikaze style existence, certainly with all the eggs in one basket

and a fine line separating success or failure. The pursuit of that rarely

attained harmony between clay, surface quality and fire is possibly

my major motivation. The end result to most is an intangible abstraction.

In a society hellbent on automation, it carries little validity or relevance,

except maybe to a handful of personalities who somehow, in the midst

of it all, retain some element of vision. Compromise has both a negative

and a positive terminal. To take the negative terminal and consciously

nurture it into the positive terminal of blend is one aspect of this

vision immediately applicable to the definition of Quality, if Quality

is ever definable. If a blend is designed to bring together the best

of the two, then surely this is a move towards that Quality. In a sense

I am looking to justify it all in one way or another, and Quality is

the only justification as all the others are seemingly created to satisfy

the ego. After all, it is a purely self indulgent passion. On the horizon

however rapidly approaches subtlety wearing the clothes of warmth, colour

and touch. The pot still has its place.

If that pot is a direct product of the personality, and the personality

is directly influenced by its environment, then logically the pot becomes

a straightforward breathing expression of the surroundings in which

it was created. To a greater part the constitution of these surroundings

consists of the purely sensual and physical, but not only. One cannot disassociate state of mind and mood. Many a strange looking pot

has disgraced the exhibition rostrum when really it should long have

been condemned to a life of shards. To have been born out of tune is

not the fault of the pot. Its life, or death, is simply the responsibility

of the maker.

John Maltby once said to me he couldn't understand how a potter could

be so deeply committed to such a mode of travel as a motorcycle. Boats

were much more in keeping. I didn't disagree, and I daresay if I made

in the manner of John Maltby I would disappear in a boat for the odd

afternoon as well. However, after three years longer in the saddle than

thirteen at the wheel, the two go hand in hand to such an extent that

one without the other would be inconceivable. If I owned a boat it would

represent romanticism, the motor cycle represents the reality. Switzerland

to England is a good days ride. Its much faster and less troublesome

in an aeroplane. Just like an electric kiln. To be in Zurich and then

in London a little over an hour later with not so much as a ruffled

hair is positively unreal, relatively speaking. Nevertheless, the total

experience and the end result is hollow. In actual fact devoid of any

intrinsic aestheticism or quality. The motorcycle is ridden out of pure

necessity and an inbuilt genetic disorder that states. must have wind

in my face while on the road. In any case Bernard Leach rode a motorbike

with Hamada in the sidecar.

I remember after I had finished all the heavy work going to the forest

early every morning and bringing back a small sapling, or some moss,

or a beautiful stone and setting it in its rightful place on and around

the kiln. It all somehow fitted together. A kind of pot pourri of values

which I am forever reconciling and kneading together into a harmonious

whole. The long fire encompasses an element as potentially creative

as the initial lump of clay and that by itself presents me with sufficient

horizons for a lifetime's work.

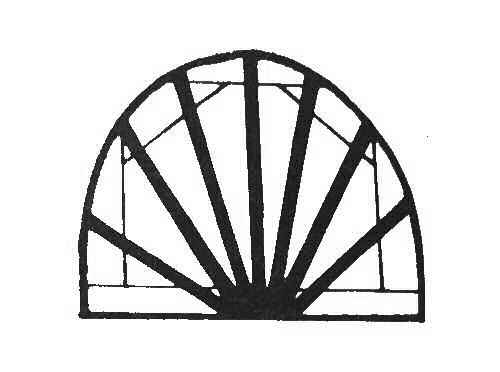

The Mule - Patrick Sargent's kiln design

Patrick Sargent

The Mule and Hutwil

The Mule from the farm

The Mule from outside

Chamber entrance

Inside the chamber

Fire Box

Bourry

Side stoke

Kiln structure - Roofing batons

Kiln structure - Roofing batons

Kiln structure - Roofing batons

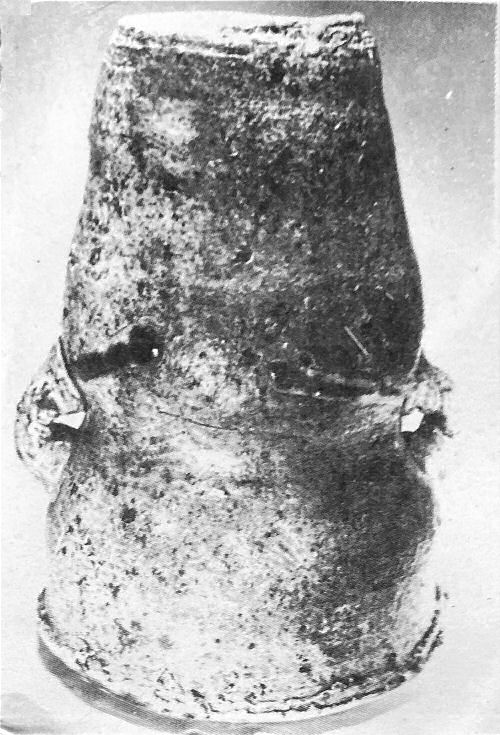

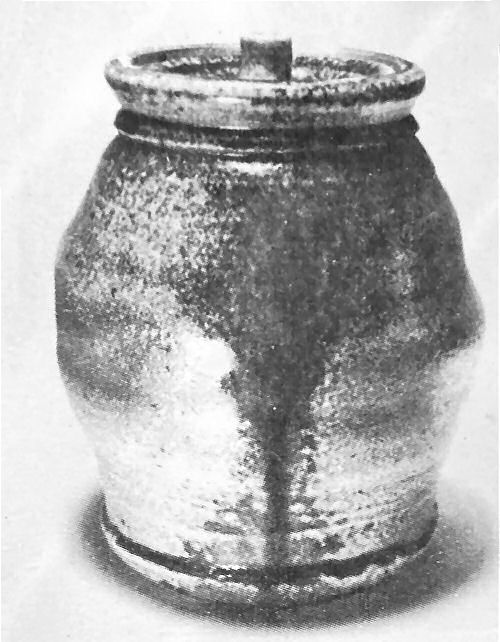

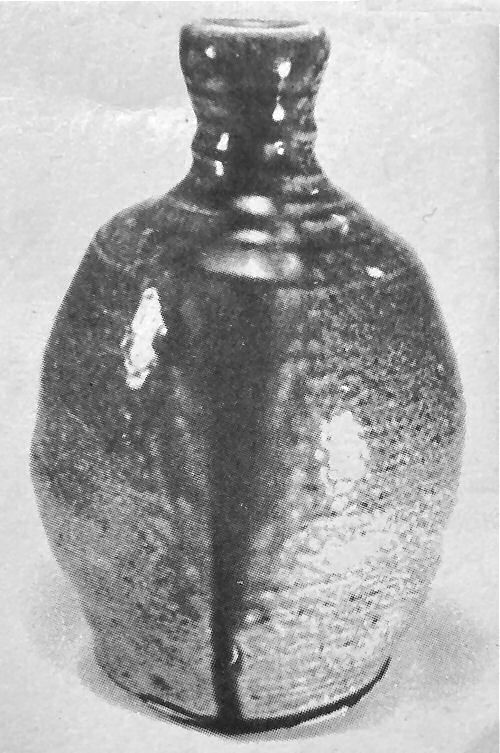

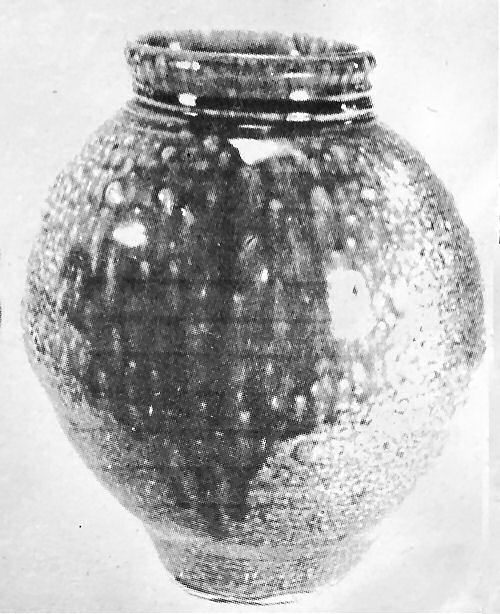

Shino bowl, 14cm

Vase 27cm

Lidded jar, 16cm

Brushed slip tea bowl, 11cm

Bottle, 20cm

Vase, 23cm

Vase, 26cm