Pottery Quarterly was the first magazine for British studio potters. Established in 1954, it was the brainchild of potter and educator Murray Fieldhouse, who had previously hoped to join the Leach Pottery but there were no vacancies so Bernard Leach sent him to see Harry and May Davis at Crowan Pottery. Murray stayed a while at Crowan before moving to Kingwood and later spending the rest of his life at the Northfield Studio in Tring.

The first edition of Pottery Quarterly included an article covering a visit to the Leach Pottery workshop which contained much useful information. Murray's widow Dorley has given permission for the article to be reproduced here. After the article are some images taken in recent years which show that many of the original fixtures and fittings remain.

Workshop Visit - The Leach Pottery by Murray Fieldhouse

(Originally published in Pottery Quarterly V1 1954, reproduced by kind permission of Dorley Fieldhouse)

Of the influences that have been brought to bear upon craft pottery during the last thirty years that of Bernard Leach has dominated. And it is proper that the first article in this series should concern itself with his brainchild.

The tremendous impact of Leach at a time when the vitality of the earlier pioneers of the movement was spent is now little appreciated. But it is easily measured by the fact that, although in 1920 he was regarded as progressive and his work highly experimental, he is now largely regarded as the more conservative influence.

Most of what he has said and done has now been assimilated in this country, although his missionary zeal is still felt in the U.S.A. and other parts of the world. It has diffused into and been accepted by the movement to such an extent that some would only recognise his ability to formulate, better than others, inherent truths. Certainly new influences in this ceramic epoch are merely qualifications of his own, and are of minor significance: "Seeing the particular in the general instead of the general in the particular", as he no doubt would put it; in fact, leading to high feelings only if wholly exaggerated.

"To Leach or not to Leach?" is not the question. For one sees the work of any young potter growing out of him quite without its author knowing it. Whether more or less deliberate imitation of his work by those who have not spent considerable time in the Leach workshop is healthy or justified is quite another question, and one which readers may care to discuss. It is the conviction of one of our most distinguished retailers that the practice is so dangerous as to outweigh much of the good that Leach had done.

Bernard Leach, son of a colonial judge, was born in 1887 in Hong Kong. At ten years of age he came to Beaumont College, and in 1903 was studying drawing and painting at the Slade under the disciplinary influence of Professor Tonks. After a few years in a bank [HSBC}, he went to the London School of Art, where John M. Swan was teaching painting and Frank Brangwyn etching.

In 1909, fascinated by his childhood memories and the writing of Lafcadio Hearn, he returned to the Far East, to Japan, as an art teacher, where, besides lecturing and teaching design, he gave the first demonstration in Japan of etching. Leach describes his introduction to pottery, in 1911, in his Potter's Book; how he was at a "sort of party" at which Raku ware was made; and how, taking in his hands a finished pot fresh from the kiln, he thought: "This is something I have got to do." "I began at once to search for a teacher, and shortly afterwards found one in Ogata Kenzan." (Sixth in the line of master potters who worked in the Kenzan style, but with a background of many more generations of traditional pottery behind him). "Old, kindly and poor; pushed on one side by the new commercialism and living in a little house in the northern slums of Tokyo." It was here that Leach persuaded his architect friend Tomimoto to try to throw a pot - both little knowing at the time that they were to become recipients of the certificate of proficiency that made them the only heirs to the title of Seventh Kenzan.

Later, Leach set up his kiln at the artists' colony of Abiko, but also worked for periods at other kilns, where he produced as wide a range of wares as blue and white, raku, overglaze enamels in addition to the temmoku and celadon in which he has gained so much distinction. His studies also took him to Korea and to China, the former country ultimately providing the maturing influence on his work. This, says Dr. Yanagi, the leader of the Japanese craft movement, who was in this country last year at the Dartington Conference, is not surprising - for Leach is for the austere gothic, and yet what he makes is intimate and warm. He has never been an artist of an excessive or repulsive nature.

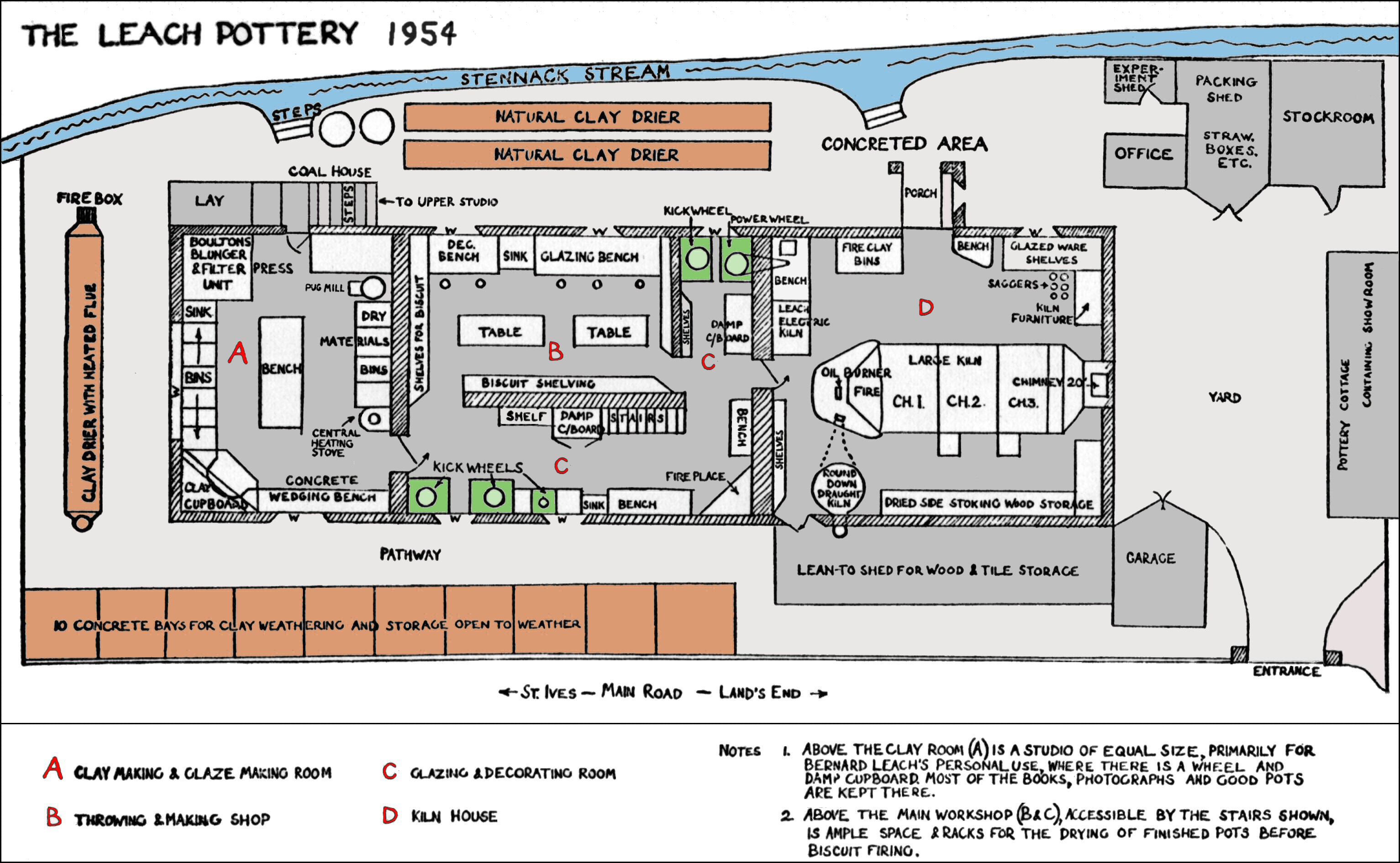

Leach had been in Japan about ten years when, in 1920, at the age of 33, he returned to England and set up a workshop at St. Ives. Soon he was joined and assisted by the young Shoji Hamada, who also had been absorbed into the craft and was from the pottery school of Kyoto. In a field beside a stream they built a pottery more after the style of the individual artist's studio than the country workshop. It comprised a small two chambered climbing kiln on the same site as the present one, and the workshop extended as far as the existing glazing room. They were assisted by a local builder's labourer, George Dunn, who remained with the pottery until his death in 1949. Entirely raku and individual stoneware was made until 1923.

It was in 1922 that the pottery was joined by T. Matsubayashi, engineer, chemist and potter of the thirty ninth generation. The disadvantage of the existing kiln was its size, which was not conducive to efficient performance. And it was Matsubayashi who rebuilt it with three chambers for longer service; working slowly and alone for nine months. Each chamber measured 6 ft. high and wide by 4 ft. deep, and the kiln held an average of a thousand pieces. Fired with wood, this kiln took about 35 hours to reach 1,250-1,300oC. About 24 hours of this time were spent stoking the first chamber with wood in the main furnace. Logs of dry pine were used, about two feet long; two or three pieces fed first into the firemouth every fifteen minutes and, after two or three hours, working up to a dozen logs every four minutes in the stokehole. When maturing temperature in Chamber I was reached, after about 23 hours, a soaking heat was maintained for 1 hour. By this time Chamber II had reached 900<sup>o</sup>C. and Chamber III 500<sup>o</sup>C. from heat overflowing from Chamber I. Side stoking then began, the heat entering Chamber III, if it contained biscuit ware, and if not was diverted into the chimney.

This same kiln is used today at St. Ives, but is now oil fired. The change involved reduction of the firemouth opening, from 150 to 16 square inches, and insertion of a central wedge of brick in the combustion chamber (to spread the narrow flame) together with the special refractories required to stand the intense heat. The kiln was almost completely rebuilt in 1952 by David Leach including the relaying of the foundations. The flues were enlarged in the combustion chamber and better refractories were used, but no change was made in the basic design. A firing today [1954] takes 24 hours; wood fire increasing in the main firemouth for the first two hours; change to oil burner after the firemouth is thoroughly warmed up. Fire in an oxidising atmosphere for nine more hours until 900oC is reached in the centre of Chamber I. Change to reduction with large flame showing when blowholes in Chamber I are opened. After 16 hours Cone 10 (1,300oC) on top of the saggar bung, and Cone 8 (1,260oC) at the side spyhole are half over. Chamber I is fired till the Cones are down by adding wood side stoking to decrease oil consumption at the burner. This lasts for approximately 1½ to 2 hours making the total firing time of Chamber I, 17 to 18 hours. This last 12 hours of wood firing is done primarily to create a wood ash which is carried up the kiln on to all exposed ware by the strong draught. Unglazed exteriors become toa sted in a manner similar to salting. During this final period the atmosphere is an alternating one every few minutes. At the start of the wood stoke there is smoke and flame dying away to clear oxidised flame and then repeated.

When Chamber I is finished the oil burner is moved to the side stoke opening of Chamber II, which is at about 900oC. The main firemouth is opened to allow air to run through, which is preheated by the time it reaches the oil flame. Chamber II rises to 1,300oC in about six hours. Wood is again introduced during the end of the firing.

The kiln today holds about 2,800 pots, 1,200 biscuit and 1,600 gloss, one third of these being placed in saggars and the rest open fired on the shelves behind saggars in Chambers I and II.

Another climbing kiln was built recently at Charnwood Priory by Vincent Ely, with the assistance of Mr. Heber Mathews, of the Rural Industries Bureau.

In 1923 Hamada returned to Japan, and Matsubayashi returned a year later. By this time the pottery was receiving recognition, and between 1920 and 1931 several one man exhibitions were held in Bond Street and its vicinity. In addition, work was shown in international exhibitions at Wembley, Paris, Milan and Leipzig.

Yet in 1921, when Leach published his "Potter's Outlook", it was clear that the many difficulties facing the individual artist craftsman were more likely to be solved in a movement towards group work. A team of craftsmen producing useful wares at moderate prices, to be retailed in selected shops and small galleries of sufficient taste and discrimination, was obviously a more healthy springboard for the reintegration of the crafts into society than the expensive precincts of Bond Street.

A standard useful ware was the refore evolved in Slipware and individual pots only in stone ware up to 1939. The slipware, production of which ceased in 1938, was available in approximately 40 different standard shapes. The body consisted of:

and was decorated with:

and mixtures of these for intermediate colouring. The slipware was fired in a round updraught kiln built in 1925 and again in 1930, after the pattern of diagram p.181 Potter's Book, with shelves forming the segments of a circle. The kiln was preheated with a pa raffin dripfeed into a tin of sawdust for 2 hours, and the firing, to a temperature of 1,050oC, took 12 hours in all. The St. Ives slipware glaze ultimately consisted of litharge 3 parts, red clay 1 part, flint 1 part.

In 1934, an increasing amount of slipware was made, involving sometimes as many as a dozen firings without a break. Laurie Cookes and Harry Davis were at this time in charge of the pottery and working with tremendous energy, carrying out samples, taking orders, and setting out immediately to execute them.

During this time Bernard Leach was again in Japan, where he had been invited to assist with a national craft movement. With Dr. Yanagi as leader, a group of craftsmen travelled 4,000 miles lecturing and planning, and were ultimately rewarded with the building of a national museum of folk art.

Leach and his American friend Mark Tobey were financed in this visit by Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst, of Dartington. As early as 1924 Leach had been invited to transfer his pottery to the Dartington Estate; and, though not feeling able to uproot at St. Ives, he did in fact intermittently teach at Dartington. Later, after returning from his second visit to Japan, he lived for a while at Dartington while working on A Potter's Book. During this period, David, Bernard Leach's son, who, in 1930, had decided to join the pottery, was in charge after a two year course at the North Staffordshire Technical College, with a free hand to carry out a three year development plan.

During his years as an apprentice David Leach was increasingly convinced that a long term view was essential to the healthy survival of the workshop if his father's creative capacities were to be established and given continuity. He saw that the way in which he could most help was by becoming a good practical potter and concentrating upon those aspects of the work where lack of technical knowledge was causing heavy losses of good creative work. From 1937 to 1940 he was responsible for introducing oil firing and electric test kilns, making a systematic series of glaze and body trials. Boy apprentices were taken and trained in the making of and increasing the number of standard stoneware shapes, subsequently justifying a catalogue. Bernard Leach did not return to St. Ives until 1940, but the shapes for repetition, for the most part, originated from his conceptions.

"During this period," says David Leach, "I thought little about my personal work, feeling that my first attention should be given to the building of the team and the practical establishment of the pottery, which must combine economic stability with good craftsmanship. I thought of my father as the creative force. I had a deep urge to make my own pots but no great impatience about it. This came later."

With the installation of the oil burner, stoneware temperatures became obtainable with little fatigue, and it was decided to turn the standard ware over entirely to oriental stoneware and porcelain, as being technically more amenable to the conditions of modern life. It is the feldspathic stoneware and, in particular, the celadon and temmoku types, for which the Leach pottery is best known. For some time the pottery depended for its stoneware body upon local materials - a red clay together with feldspar, china clay and sand. Later, Pikes silicous ball clay was introduced in compounding the porcelain body; then also into the stoneware body, making it more workable and less likely to blister if slightly overfired. The local red clay could still be added if a darker body was required, but the addition of red sand provides a pleasing texture. Today [1954] the standard stoneware body consists of:

This recipe gives sufficient plasticity for good light throwing and stands up well at stoneware temperatures, with sufficient vitrification if the sand is fine enough. It has excellent drying properties and a good relationship with glazes.

At one time, the bodies were prepared by sieving the weighed materials into a barrel and siphoning off water as they settled. The sticky mess was dried out in a trough made of fireclay bats. Today all clay is mixed in a 24" Boulton Blunger and then through a vibrating sieve. Most of the stoneware body is still dried in troughs the sand being added to the slip. A filter press is chiefly used for the porcelain body; if used for the stoneware, then sand is added at the pug mill.

The clay is finally tempered up by wedging and kneading by the throwers to their own personal preferences. The standard stoneware is made in a number of different finishes, depending upon the shape:

1. Celadon and temmoku inside only, grey stoneware body outside.

2. Temmoku glaze all over.

3. Celadon glaze all over, sometimes with incised decoration in body.

4. Opaque glaze on grey body, decorated with cobalt or iron.

5. Oatmeal glaze, decorated with cobalt or iron, or dipped outside in thin temmoku glaze or iron wash.

Other glazes are used for individual work, and these, together with the standard glazes, are used for a variety of decorative effects, one over another, for example, with wax resist or carved upper glaze pattern. Sgraffito iron slip over both stoneware and porcelain, usually under the oatmeal glaze. Decoration is chiefly abstract free incising and flowing calligraphic brushwork. Particularly noticeable in the decoration of Leach pottery is the feeling of easy rhythmic execution that is conveyed.

| Leach Pottery - Glaze Formulae | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tenmoku | 5 | 10 | 10 | 40 | 20 | 13 | |||

| Celadon | 12 | 13 | 26 | 20 | 2½ | 26 | |||

| Oatmeal | 23 | 5 | 2½ | 52 | 5 | 12½ | |||

The standard glazes above are used for both stoneware and porcelain bodies. The latter body consists of: china clay = 25, felspar = 30, black ball clay = 33, water ground quartz = 12. The present proportion of stone ware to porcelain is 4:1, and the work cycle (three weeks between firings) is as follows.

Everyone takes part in the kiln unpacking, sorting and

counting. This, together with the cleaning up, takes a day. Frank Vibert,

the secretary, calculates the value of the kiln and simultaneously David

Leach prepares the making list. This list of 2,000 pots is divided between

the throwers, some of whom will throw for only ten days. It is prepared

with a number of considerations in mind:

1-Pots required for orders

2-Pots required to replace stock

3 -Kiln combination for economic packing

4- Variety, to extend the throwers' sensibilities and capacity to throw

full range.

While the throwing is proceeding the biscuit from chamber II is glazed and

decorated by one or two people. A week before firing the two best throwers,

Kenneth Quick and William Marshall, have finished their quota and are free

to commence kiln packing. The last chamber is left until the day before

the firing, so that the pots are thoroughly dry. Horatio Dunn, son of George

Dunn, divides his time between packing and clay making, being assisted in

the latter work by the junior apprentice, Scott Marshall. The making list

is flexible enough to allow each thrower half a day a week for his individual

work. David Leach feels that the present way of working has proved itself

and is good, but he would like in the future to give more opportunity to

the team in the creative field of design, which heretofore has depended

upon the inspiration of his father. "A tradition has been passed on

which releases creative potential and can provide the team with opportunity

for expression."

About one third of the wares of the pottery are disposed of by seasonal selling at the pottery and a shop in the town. The rest by mail order, exhibitions and in discriminating stores. The one man shows are of publicity value, but only just pay for themselves. Last year's production was 22,000 pots, the retail value approximately £6,000.

Before concluding an account of the many practical achievements of the Leach Pottery, mention should be made of raku ware, which was produced at demonstrations in the early days and did much to establish a nucleus of enthusiastic patrons. The practice was to have a slipware firing going so that by 2 p.m. it had reached a temperature of 800oC. at the top. Biscuit pots in a refractory body were priced and displayed on shelves for visitors to paint with raku underglaze colours. The decorated pots were taken out to Bernard Leach who dipped them in a raku glaze: white lead 66, quartz 30, china clay 4. After drying, the pots were placed in the kiln by removing two bricks in the crown. During the firing the visitors had tea and the colourful pieces would be ready for them to take away.

Raku ware has been utilised more recently by Mr. John Bew, demonstrating in our leading department stores and using a Grafton kiln with a special fireclay door from which the glowing pots could easily be removed and so evoke greater interest among the general public in the work of the craft potter.

Bernard Leach is again in Japan, and it is hoped to publish in Pottery Quarterly some notes on his impressions on his third visit, which followed a year of tremendous achievement the publication of his A Potter's Portfolio; an International Conference of Potters and Weavers, held at Dartington (largely through his inspiration and leadership), and, conjointly, an exhibition of Thirty Years of British Craftsmanship. Arranged in collaboration with the Arts Council, this exhibition moved from Dartington to The New Burlington Galleries and then to the provinces. At the same time, Leach and Hamada, whose work had not been seen in this country since before the war, had a two man show at the Beaux Arts Gallery. Leach left before the exhibition was over for a lecture tour of the United States, and then on to Japan. Writing at that time, in a leaflet sold with his exhibition catalogue, Leach said: "This small workshop is an experiment both in aesthetics and in the human relationship that lies behind that kind of work which employs feeling as well as intellect and manual skill ... An exceptional degree of faith and trust held in common is essential to that end, and a willingly accepted leader is necessary who is good enough man and potter to draw out the latent capacities of each member of the group From the date of my departure my son David will be in charge of this pottery ... The freeing of latent talent, the release of communal design and the acceptance of greater mutual responsibility remain to be worked out."

Recent Views

Here are some recent views of the areas A to D in the 1954 plan plus the Upper Studio and the outside areas

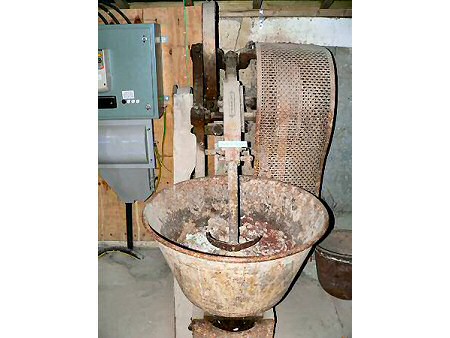

A - Clay Making and Glaze Making Room

Pug mill, ball mill and sieves

Dry materials bins

Boulton's blunger

B - Throwing and Making Shop

C - Glazing and Decorating Room

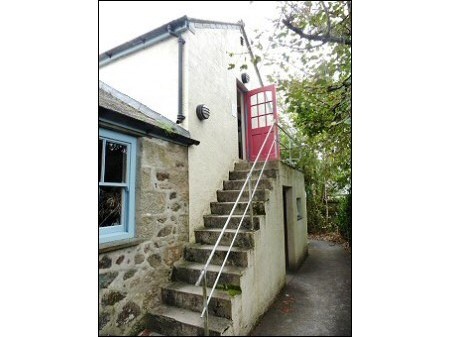

Stairs to storeroom

Fireplace

Scuttle - Bernard Leach's seat at crib

Towards the fireplace

D - Kiln House

Climbing kiln

Climbing kiln burners, two smaller kilns

Small kiln (site of the round downdraught kiln)

Electric kiln

Upper Studio

Outside Area

Clay weathering bays

Remains of one end of the clay drier in front of the pottery building

Stennack steam at the rear of the pottery buildings

Steps to the upper studio (Bernard Leach's studio)