I have reproduced the article here...

Although the products of the craftsman potter are fairly well known, little work has been

done on his working techniques, even though they appear to have varied considerably

from one area of the country to another. In 1900 there were still about a hundred coarse

earthenware potters working throughout England, but their numbers have been reduced

drastically over the last few years, so that there are now only two such potteries in full

time commercial production, the Farnham Pottery in Surrey and at Truro in Cornwall.

History

The earliest documentary evidence for potting on this site is a deed of 1845 in which

Lord Falmouth leased to Edward Dennis Tucker of Truro, Potter, five cottages known as

the Quakers' Tenement at the foot of Chapel Hill. The pottery had been working on

the adjacent site for a considerable period, however, for the remains of a late seventeenth

century brick-lined kiln were discovered when foundations were being cut for a new

kiln in March, 1968. From the 1840s Tucker worked the existing Chapel Hill Pottery

under his own management, but in 1873 he went into partnership with William Henry

Lake, the pottery at this time making a wide range of wares including salters, pans,

bussas, pitchers, ridge tiles, and cloam ovens. Shortly after entering into the partnership,

Mr. Lake took over the concern completely, and it is now managed by his grandson who

makes studio pottery in addition to some of the more saleable traditional wares.

Potting

Clay, the basic potting material, was originally worked in the Truro area, a good clay

lying beneath the meadow adjoining the pottery, where Bosvigo School now stands.

From the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, however, most of the potting

clay used in Truro was imported either from St. Agnes, on the North Cornish coast, or

from North Devon, where it was of a far superior quality. In his biography, Fishley

Holland of the Fremington Pottery near Barnstaple has described how Fremington clay

was shipped from Appledore Quay to Truro, even as late as 1914. At the pottery, where

a fresh load of clay arrived once a fortnight, the potters had to knead the clay mechanically

in a pug-mill to render it down to a smooth and uniform condition before throwing it

on the wheel. The pug mill itself was in the form of a tall wooden cylinder inside which

rotated a central spindle mounted with a number of sloping knives which sliced and

compressed the clay until it was extruded as a uniform strip from the cylinder's base.

Now this process is carried out by modern machinery, but the base of the wooden pugmill

still remains at one end of the kiln house, where it is surrounded by a twelve-foot

diameter cobbled walk which was used by the horse when operating the old machine.

Once the clay had been pugged it was wedged by hand to remove any remaining air bubbles,

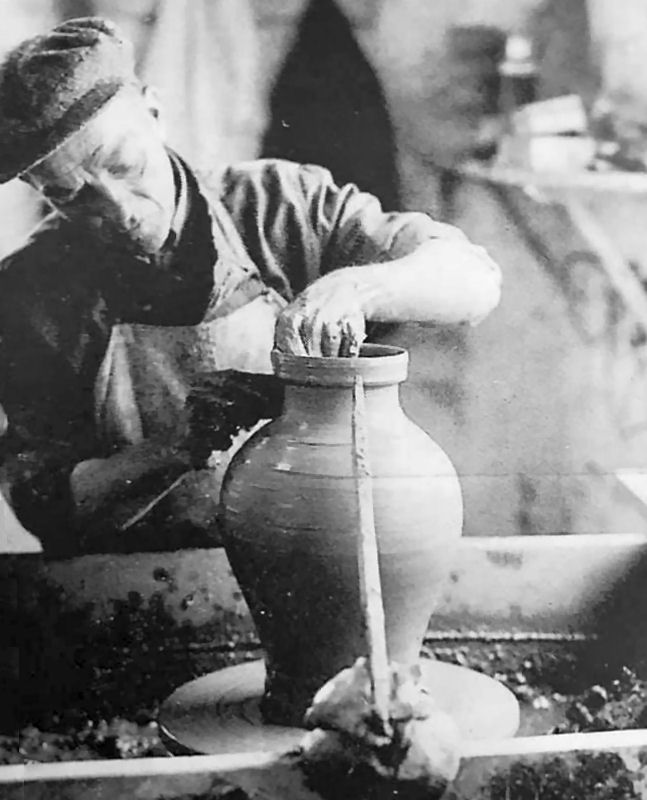

and divided up into balls of a suitable size for the work in hand. Throwing then commenced,

the clay being banged down on top of the potter's wheel, splashed with water as a lubricant,

and squeezed into concentricity by the potter's hands as the wheel rotated rapidly.

After being hollowed and drawn up into a cylinder the pot was brought to its final form,

sliced free from the wheel-head with a taut wire, and placed on a long board with its

fellows to be carried into the drying room. The old wheel at Truro, dating from the

middle of last century at least, was powered by a 'rope-boy'

who turned a large pulley made from an old cart wheel, from which a loop of rope

extended to a small pulley mounted on the axle of the potter's wheel, some 9' away.

In many ways this was an ideal potter's wheel, for, with experience, the rope-boy could

vary the speed of rotation required by the potter with no prompting, thus leaving the

potter free to shape his pots with the maximum speed and efficiency. Early this century,

however, the framework of the old wheel was stripped of its old pulley arrangement, and

re-fitted with extended legs and cast-iron gearing to enable it to be used in a rather more

confined space.

Having been shaped on the wheel, the pot had to be carefully dried, for if it gave off

its water too quickly it would warp and crack, while a damp pot would undoubtedly

shatter when exposed to the heat of the kiln. The drying took place in a room close to

the kiln which was equipped with a series of wooden racks on which the boards of damp

pottery could be supported. Here the live 'glauze', as the charcoal from the furze fires

of the kiln was known, was placed in long heaps on the floor, the gentle heat emitted

over the next three days burning being just sufficient to dry the wares without any risk

of their being damaged.

Firing

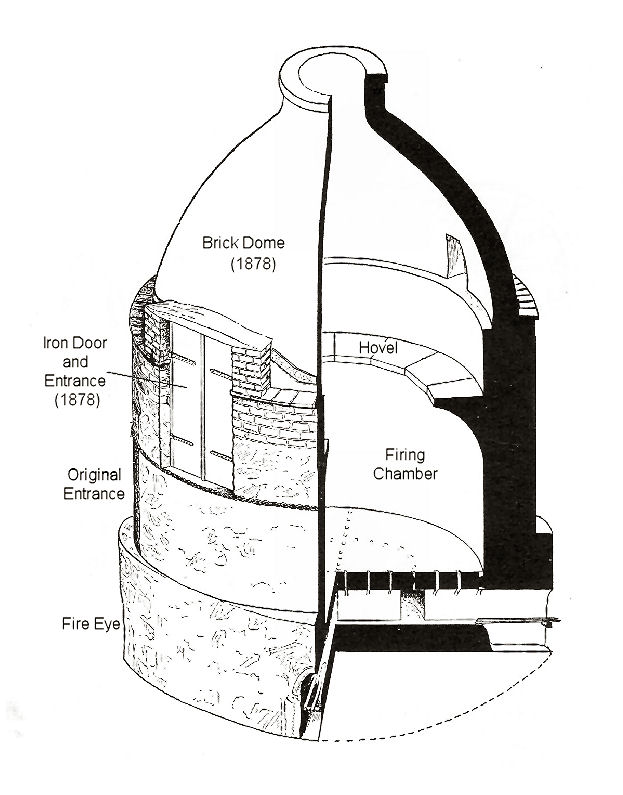

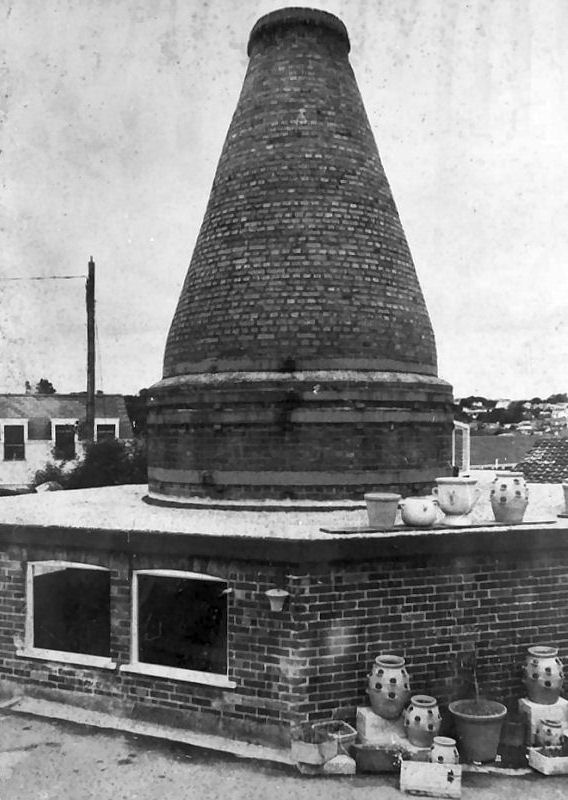

The oldest kiln still standing at Lake's pottery, Truro, has been modified considerably

since its erection, in the late eighteenth century. The original kiln consisted of a tall

masonry cylinder with a cantilevered walk-way or 'hovel' around the top,

and a completely open roof. When firing this kiln, the pottery was loaded into the firing

chamber until it was full, and the top roofed over by means of a number of specially

made clay slabs topped with a final layer of broken potsherds etc. The kiln was then

fired with furze and wood to a temperature of 950°-1000°C. In hamber Edward Tucker

and W. H. Lake, who were then partners, erected the existing tall brick dome over the

old open topped structure, transforming it into a fairly standard updraft kiln. This change

was due to Mr. Lake's visit to Wales, where he had seen the superior brick-domed kilns

of the Ewenny pottery. Instead of completely abandoning his earlier method of topping

his kiln, however, Mr. Lake still continued to build up his traditional slab and sherd

topping within the new cone, this unusual method being used until the kiln was replaced

by a new coal-fired kiln in 1943. As the kiln was showing sings of decay when the writer

visited the pottery, the opportunity was taken to record both its structure and its working

while this information was still extant.

The potters first task was to obtain the furze necessary for the firing. Originally this fuel alone had been used, but by the opening years of the present century the price of furze had made it more economical to use coal for the initial firing, although furze was still retained for the final 'flashing' of the wares. The furze itself was either cut by the potters themselves on Potter's Down, a short distance outside Truro, or was purchased from professional cutters, many of whom were employed by such landlords as Lord Falmouth to clear the rough ground round about the neighbouring villages. In 1910 the price was approximately 10 shillings per hundred faggots, rising to £3 per hundred in 1942-3. On arrival at the pottery, some 2,000 faggots were stacked inside the west end of the kiln house to eaves height, ready for use, while a further 2,000 were formed into a tall rick in the pottery yard. As the year progressed the furze dried out slowly, the particular state of dryness being reflected in the colours of the glazed pots when they emerged in final form from the kiln. A pot fired in the spring when the sap was rising was characterised by a dark green to yellow glaze, mottled with a few pale orange patches and dark dots where particles of burning furze had settled on the glaze. Pots fired in June presented a fairly even khaki colour, while those fired from August onwards were of a particularly rich red-brown.

Having laid in a sufficient supply of coal and furze, the potters proceeded to pack the kiln, passing in the 'green' (i.e. raw) ware through the iron doorway at first floor level. The first pots to be placed in the kiln on Monday morning were pitchers, each one being stood in an inverted position on a 4" x 7" tile, care being taken to ensure that the pitcher's rim overhung the side of the tile, thus allowing the rising flames to enter each pitcher to give a good internal glaze. The top of the pitcher handles were also placed centrally on each tile, this being the section of the pot best able to withstand the weight of the rest of the kiln load. Once the first layer of pitchers had been completed, a second, third, and fourth layer were then added, the top of the handle of each pitcher resting centrally on the upturned base of the one beneath it for maximum strength and stability.

At this stage, with the first 5' of the firing chamber fully packed with pitchers, the first day's work was completed. On Tuesday, low fires of coal and ashes (the latter being obtained from either the Railway Engine sheds or from previous kiln firings) were lit in the four 'fire eyes' or fireplaces, the gentle heat slowly drying out the stacked wares to enable them to receive the weight of the remainder of the load. By Wednesday morning the fires had died out, having consumed some 10 hundredweight of ash during the Tuesday night to bring the kiln to such a temperature that the packer's candle frequently melted an trickled away uselessly. At this stage the bussas and plantpots were inserted, the packer standing on a few short planks of wood placed on sacks on the centre of the stack of pitchers. Working inwards from the perimeter, he packed each piece in place with trigs and piecrusts until he was completely surrounded by his wares to the level of the protruding hovel ledge. Two long planks were then placed across the kiln at this level to enable the packer to climb out of the stack, leaving behind him the short planks and sacks on which he had been standing. Then, with his partner gripping his ankles, the packer hung upside down into the central hole, thus retrieving his planks and sacks for future use, and also packing further plantpots and bussaz in place to complete the second stage of the packing.

On Thursday morning work started on the top section of the kiln, building up the wares above the level of the hovel or walk way, working from either the long planks across the kiln or from the hovel itself, a range of various wares was built up to a height of 18 in. above the level of the previous stack. A circle of 'backs', tiles some 18" high by 12" wide by 2" in thickness, was then erected around the ware, the bottom of each back resting on the inner ledge of the hovel, and the whole circle tied firmly in place by a stout iron plough chain. Further wares were then added, three more staggered courses of backs being chained around them to contain the stack before it was roofed over with a layer of old potsherds. Having sealed all the joints between the individual backs with mud taken from the river, the iron doors were closed, and the kiln was ready for firing.

The firing proper commenced on Friday morning, three to four tons of coal being stoked into the kiln during the following ten hours, this being just sufficient to bring the lowest tier of backs up to a dull red heat. At this point the coal fires were rapidly raked out, the firebars knocked out, damped down, and cleared, and furze fires started in each of the empty fire-eyes. During the next five hours between 500 and 600 furze faggots were consumed, one stoker being required to tend each of the four fire eye. Two assistants were also employed to supply the necessary fuel to the stokers, and also to assist in raking out the glauze (i.e. 'glows'; the red hot furze embers) every 55 minutes or so, this being necessary to allow sufficient oxygen into the kiln to ensure a good glaze. It was particularly important that the kiln should be fired evenly, for it was possible for a stoker using extremely dry furze to bring his quarter of the kiln up to temperature two hours before his fellows, while a slow stoker could slown down the whole process. By maintaining an even rate of stoking, however, and damping down the furze whenever necessary the temperature was evenly raised until the top row of backs glowed to a dull red colour. The quality of the stoking rapidly became apparent about this time, for, with a sudden 'whoosh' the fire broke out of the top of the stack, flames shooting upwards as if from a blast furnace. An even distribution of flame and an even glow in the sky showed that the stoking had been carried out successfully, while a thin streak of flame proved that a wide range of temperatures still existed within the kiln. If all was well, the potters then checked if the glazes were fluxed to a satisfactory degree. For this purpose two pitchers had been placed on the top of the stack, one with its mouth facing the window, and the other with its mouth facing the door. Taking a long iron rod the potter carefully knocked away the protective sherds placed over the mouth of each pitcher, next inserting a glowing ember into each one in turn. From the reflection this produced he knew exactly when the glaze had been perfectly fired.

By Friday night or Saturday morning the firing was usually completed, and the kiln, with its four fire-eyes sealed up, could be left to cool over the week-end, the finished wares being withdrawn on the following Monday.

The Wares

The wares made by Lakes of Truro were particularly designed to meet the requirements of the local fishing and farming communities. Besides producing the pitchers, pans, wash-bowls, baking bowls, chicken fountains, and ridge tiles made by almost every country pottery they also produced a large number of more specialised items, the most important of which was the bussa. This was a tall pan in which pilchards were salted down for preservation, a layer of salt first being strewn in the bussa, this being followed by a layer of pilchards, and further salt, the process continuing until the pot was full, when a piece of flannel was placed across the top, to stop the fish from going 'rusty'. A heavy stone was then put on top of the whole to press the pilchards in the salt for pre- servation. Bussas were regularly supplied to the fish-cellars of Penzance and Newlyn, but the demand became particularly heavy whenever an unexpected glut of pilchards was landed at either of these ports. When news of such an event reached Truro the carters from Lake's and Venn's potteries raced each other down to the coast with loads of bussas, each trying to capture this opportunity for additional sales, but it is remembered that the Lake's waggon always won, as their competitor's horse invariably halted at every public house along the route from sheer force of habit.

Salting pans were also made for the preservation of beef or pork joints, the technique being to make a brine by adding enough salt to the water to enable a potato or an egg to float therein. The joints of meat were then submerged for four weeks or more in a wide salting pan full of this brine, before being wiped dry and hung, or possibly smoked, ready for use.

Cloam ovens were also made at Lake's pottery, the last ones to be made in this country being produced here in 1937. These ovens were tempered with quartz crystals (as opposed to the coarse gravels used for oven-making by the North Devon potters) to render them fire-proof, their manufacture being a matter of considerable skill. In form they resembled a tall dome, a broad rectangular frame modelled on to one side near the base enclosing a detachable over door. In use, a furze fire was kindled within the oven, this being gradually built up until the top of the oven was hot enough to cause glowing sparks to form at the tip of a twig rubbed over its surface. At this point the glauze was raked out, the bread inserted, and the oven door carefully sealed in position with river mud or clay, after which it was left for a sufficient period for the bread to bake.

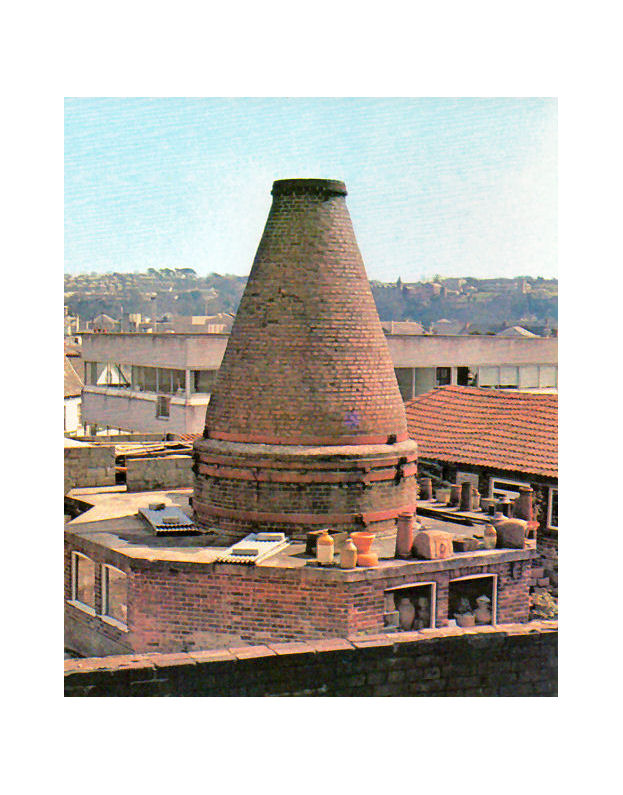

The Wheal Martin museum near St. Austell has an exhibit featuring Truro Pottery, here are a few images.

Some old images of Truro Pottery