Mashiko, the El Dorado of many Western potters, is a small

unpretentious village which has produced the kitchen ware for

Tokyo for about 250 years. It came into existence with the

establishment of Tokyo as the new capital, and potters travelled

north from one of the best old potteries in Japan (Karatsu, now

extinct) to found it on the remains of a pottery of a prior civilization.

The mountains in this area are gentle and well wooded and the

valleys are broad, making good rice fields. The potter and his wife

and family raise their own rice and foodstuffs as well as carry on

their work of potting. There is rarely a day when one does not see

a swirl of smoke rising from some kiln being fired. It was in this

simple remote community that Shoji Hamada chose to establish

himself upon his return to Japan after having worked with Bernard

Leach when the St. Ives pottery was being established. Hamada

could have had a much higher position had he chosen to make his

life in one of the cities, for he was a graduate of one of the best

technical schools of Western ceramic science in Japan and had

served as a professor before coming to England to work with Leach.

But he wisely chose the more wholesome background of a

traditional rural pottery and spent the first five years developing his

own work whilst using the workshops of these potteries. Slowly

and surely he grew, acquiring inner strength and assuredness before

he built his own kiln and workshop. Now his home is quite

imposing. His houses, examples of the best architecture of the

area, are built of adobe-like stucco and huge wooden beams with

heavy thatched roofs two feet thick. His gardens are informal;

and tucked inconspicuously along paths are outstanding examples

of Korean sculpture. His love for the beauty of the traditional

buildings has led him to acquire them, but his life has remained

simple and over all hangs the air of work as related to life, beauty

coming from the daily way of things.

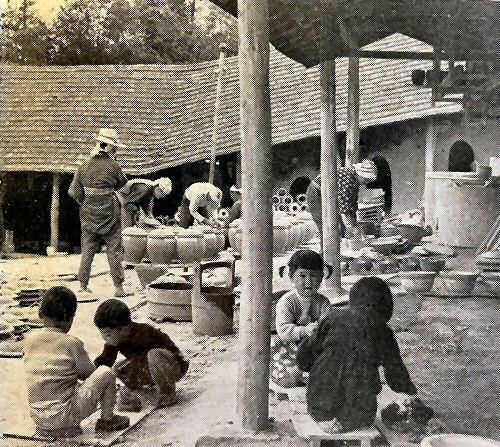

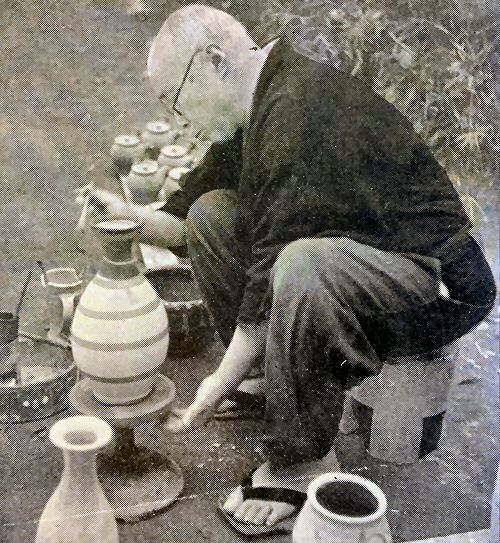

The day of my arrival at Hamada's was a memorable one, for

they were in the midst of glazing and stacking his large eight-

chamber climbing kiln. Never had I seen so many pots being

handled in so deft a manner. Hamada, his two sons and about six

workers were in a veritable forest of pots.

The workshop is about 30 x 100 ft. long with a larger ground

area in front where pots are dried, and down a steep slope are his

largest kiln and another storage building. The working area under

the kiln shed is about 50 x 50 ft. The entire ground space of all

buildings and the adjoining area outside and along the sloping path

was thickly covered with boards full of pots! Nowhere was there

a clear pathway for walking; men with boards of pots over their

shoulders were nimbly stepping over and around other workers with

boards-a nimble weaving over and under in a long-rehearsed

performance.

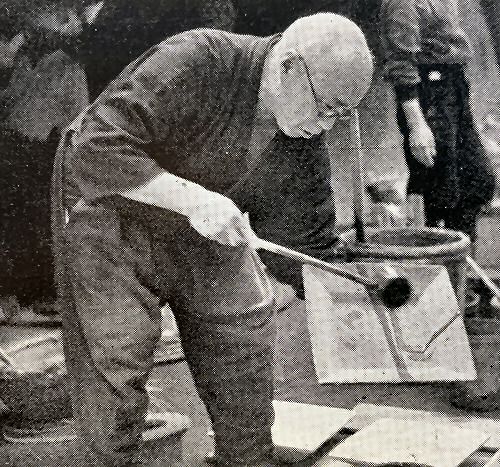

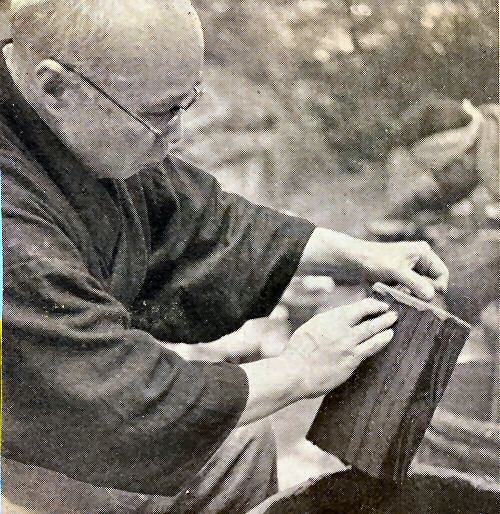

All glazing was done on the ground, either bending over large

wash tubs pouring with a ladle, dipping or squatting to decorate

and to wash the bottoms of pots. Everyone seemed to know what

to do and glided from job to job, anticipating each need and

process beforehand. Hamada does all the decoration on his own

pots and more than half of it on stock items, in addition to

indicating what is to be done to the others and instructing as to

glazes and their treatment. I watched him decorate more than five

hundred pots with wax and glazes in one day, sitting on a low stool

with pots around him on the ground.

His best pots were reserved till late afternoon, for the more he

worked the more vigour he had. The work was feeding him rather

than draining him. His decorating techniques are principally that

of glazes over glazes; sometimes over a thin yellow ochre slip, often

with a wax pattern brushed on the first glaze; and his best-known

technique is of trailing a large glaze pattern with a dipper. His

brushwork is excellent, but he uses it only in a large sweeping

pattern.

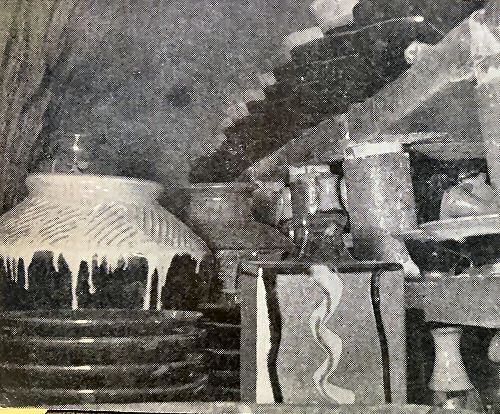

About five thousand pots were in this firing, many quite large,

and most of the glazing, decorating and stacking was done in three

working days. This number of pots represented less than two

months' work (including bisque firing) by the two throwers (who

have worked for him nearly fifteen years), his two sons and himself.

The kiln firing lasts two days, and the sight of men stoking small

split sticks of pine into each chamber successively, with the resultant

belching flames and smoke from the port holes, is highly dramatic.

The temperature reached is about 12500C. No cones are used,

temperature and heat dispersion being judged by eye. The firing is

oxydised throughout the kiln, with the exception of the first

chamber, which always tends to be neutral to reduced in the

climbing kiln. In this chamber he uses different glazes, such as

the runny treacle-like one, with the pots set on shells for stilts.

The kiln was allowed to cool a day before opening. Two full days

were needed to unload, sort and instruct the packer as to shipments;

two more days to finish grinding bottoms of pots with hand stones,

stack saggars and clean the kiln floor and working area. Hamada

owns two kilns, one of five medium-sized chambers and a much

bigger one of eight large chambers. He averages firing either one

or the other of these every six weeks. Whilst I was there he also

began his experimentation with salt glazing, using the last chamber

of the small kiln. Almost no salting has been done in Japan.

To my eyes, his work cycle represented a miracle, without

taking into consideration the quality of the ware. He prefers not

to spoil the working atmosphere by the use of mechanical equip-

ment. The spirit surrounding the pottery is relaxed and free.

Hamada has a hearty ease about him which passes on to the crew

and is reflected in the pots as well. There are few seconds, but

there is also little apparent concern over the "imperfections of

nature," and their thinking has not been influenced by our imposed

standardization. Slick uniformity is not their conception of quality.

In rural Japan there is no Sunday, work is continuous until

firings. During the kiln watching, cooling and opening there is a

relaxed period of semi-holiday before preparations start for the next

session of work.

The workshop is a long stone and plaster building with a thick,

high-pitched thatched roof. This overhangs the building by about

six feet, providing under its eaves ample space for vats of glazes and

materials and drying racks. Along the entire length of the front of

the building are sliding, paper-covered windows which give the most

pleasing light I have ever worked in. There are racks along the

back wall as well as overhead, everywhere. In the centre of the

earth floor is a bricked depression, two feet square and a few inches

deep. This, the fireplace, serves as a source of heat to dry pots,

sandals and oneself; and, as everywhere, there is a black kettle

suspended over it. Running the length of the building under the

windows is a bench-like structure about two feet high and six wide.

This built-in platform is the only working area other than the earth

floor. No other tables, stools or benches exist. Interspaced along

this structure are thirty-inch-square embrasures which accommodate

eight potters' wheels. Some are Korean type kick wheels; others

are hand wheels turned with a stick.

Clay is delivered by horse and wagon from an adjoining

claymakers' village where it has been washed, sieved and dried,

ready to be kneaded. The men mix large mounds of it with their

bare feet on the earth floor of the shop. At the conclusion of the

mixing, it is left on the floor in heaps about 3 x 3 x 3 ft. Slices of

between thirty and fifty pounds are cut off and kneaded on the edge

of the platform next to the wheel. Their manner of rolling and

kneading, though arduous, is not as strenuous as ours. They never

lift the bulk of clay, and when their final hand-kneading is

completed the resultant rolls of clay are already in a convenient

working position for the wheel. If the clay is too soft, large pats

of it are thrown against the stone wall outside underneath the

windows and a board is placed on the ground to catch it when it

dries and falls off.

In every stage of work there is a natural flow of convenience

and availability without intellectual planning and organization.

They intuitively use the elements and materials supplied by nature

around them. A wad of dried straw rolled and tied makes the best

brush I have ever seen for washing the bottoms of pots; a similar

brush is made for kiln washing, the shelves and saggars. Straw

alone is used for packing, and the packer makes much of his rope

as he proceeds. Pots are dried in the sun and wind. Glazing is

done outside, so that no thought has to be given to drying the pots

before firing in the slowly heated kiln. Miscellaneous bowls,

utensils and boards are set out to be washed when it rains. All of

this results in a kinship and a flow of the work with nature.

The Korean kick wheel is a diminutive version of the

Normandy wheel. Its construction is simple, consisting of two

circular wooden discs, about fifteen inches in diameter and four

thick, joined by four posts, making a unit about twenty inches high,

which turns on a pointed spindle set into the earth. The wheels

are located centrally in the embrasures in the platform, with which

the wheel head is level. The potter sits on the edge of the structure

with his feet (usually bare) in the hole and kicks the lower disc.

Some rotate the wheel clockwise by pulling forward with the right

foot and toes. The hand wheel, consisting of one disc about

twenty-eight inches in diameter, is invariably turned clockwise for

greater power. The same tendency has been carried to the kick

wheel, although it is not considered theoretically correct There is

much less power in both these lightweight wheels than in any

Western types; but, as with everything else in Japan, the work is

not accomplished so much by power or push. Most of the work

is done from a ten- to fifteen-pound mound of clay. Larger pots

require centring equally as much, but this is achieved by deft

persuasion rather than power.

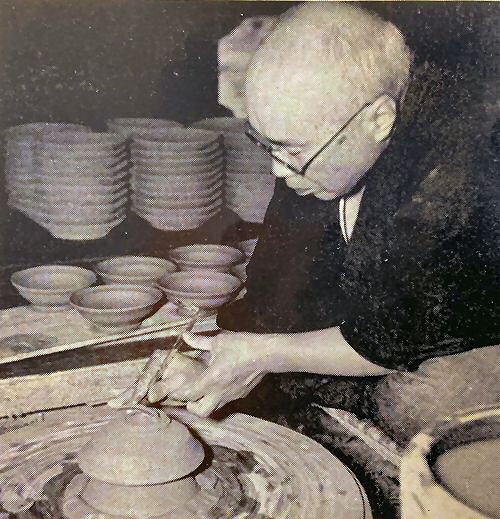

As I watched the throwing-whether by Hamada, or one of

his men, or any of the numerous throwers in the traditional potteries

along the roads of Mashiko-the realization was always the same:

the skill and fluidity of movement and the work resulting are the

outcome of an approach which is foreign to us. Their pots are not

made, they flow. This is best described by such words as ease,

naturalness, attunement, non-aggressiveness, and so on.

There is a harmony of living and working. Work is not

merely work; it is life. Whatever a man does he does with

his whole being, without self-consciousness or even awareness

of physical discomfort or fatigue. When he is throwing, he is

completely in his work; when he stops for a smoke he stops

completely. He takes long breaks for tea and chats; he plays with

the dog, watches a butterfly or picks a flower to put beside his

wheel. But there is never a half-way attitude; always an all-ness

of his whole being. This results in clean, sure movements - just

enough, without indecision or fiddling. Pots grow, are cut and set

off; grow-cut-set off with a rhythm of respiration.

When Hamada is throwing, it is obvious that he is

conscious only of the nature of the material he is using-clay-

and the form he is envisioning. There are no repressions

or regulations governing accuracy or precision relating to the

machine. He is striving for the spirit of the form in clay, the pot

comes up and at the first spontaneous burst of life he stops working

it. It may not be quite smooth, even, or centred; but these factors

are secondary and he does not sacrifice spontaneous vitality for the

sake of mechanical slickness and perfection.

When discussing glazes with Hamada (he knows more about

glaze chemistry than most Western potters) he commented to me

that on his recent tour through England and America many potters

thought him to be a simple peasant because he used only wood ash,

ground stones, feldspar and rice husk ash for his glazes, whereas

Western potters use long lists of chemicals and measure them by

molecular weight. He chuckled and said: "They think they are

being very complicated and I very simple, but in truth it is I who

am the more complicated, for I am using nature's mixtures, which

are infinitely more complex."

It is difficult to convey the full meaning of these people's

attunement to life and work; but in this atmosphere of natural

living and work one does not ask "How do you do this or that?";

one just does it, and it works. It is my opinion that Hamada was

wise enough to realize the true value of a living tradition, for it has

supported him and allowed him to grow to heights of maturity

which could hardly have been accomplished in unsympathetic.

unfertile soil.