Avoncroft Pottery 1958

It is just over three years since Avoncroft Pottery moved to its new

home, bringing its name with it. We had really outgrown our

original premises, some seven miles away. Also it was not a good

place to attract visitors, and we did not feel very secure there. Our

new buildings, grouped round an open yard; which serves usefully

as a car park, and the house in which I live were once the workshops and agent's house respectively of a country estate.

We brought all the equipment from the old pottery with us;

all, that is, except the kiln. This was a two-firemouth, updraught

which I had built originally for slipware. But in it I had been

firing high-temperature stoneware for several years, and it wanted

relining anyway. So, in some sadness, we pulled the thing down,

salvaging the best bricks, which are now in the foundations of the

new kiln. Thus we felt that we were taking some of our roots

with us; and we hoped it might augur well for the future.

We had not any great quantity of stock to keep us going while

setting up shop; so we had to hurry if we were not to starve or

lose existing contacts. Soon concrete had been laid in the workshop

and the wheels emplaced. We built benches and tables of large,

pre-cast paving stones laid on brick piers - a most useful and cheap

form of construction in a pottery. A garage across the yard was

fitted out as a showroom. This we share with a well-known

wrought-iron smith, Alan Knight, whose workshop is adjacent.

To have two crafts going on alongside each other is a double

attraction for visitors, and to some extent one kind of work sells

the other.

The big task facing us was the new kiln. This had been

designed, inch-scale working drawings made and planning permission obtained

before we moved. I had decided on a two-chamber, climbing kiln on the

principle of that at St. Ives, but differing in detail; also that, as

in the old pottery, I would save workshop space by building it outside,

merely roofing it over; but this roof has not materialised yet! The

foundations involved the removal of some twenty-five tons of soil, all

being done manually, and the laying of six tons of concrete, for which

we were fortunate to have the use of a mechanical mixer. I decided to

build the kiln in two phases. First the foundations, firemouths, chamber

I and the chimney, by which time it seemed likely our stock of pots

would be exhausted and it would be high time to get more made, fired

and sold: then to add chamber II later at our convenience, but before

the existing structure had had time to get out of shape. This all panned

out very well and, working alone except for odd mortar mixing, I had

phase one completed in three months. Work was not continuous because

time was set apart most days for making pots ready to be fired when

the kiln was finished. Also we were held up at times by the weather,

both wet and frosty. But a floodlight was rigged and on fine nights

work was able to proceed far into the dark. By the following March we

had fired - fairly successfully for a new and strange kiln. Then again

in three weeks, and we were in production again. A few months later

chamber II was added, the work taking a month to complete.

For those who wish to know more of this kiln, each chamber

measures approximately 5' high, 4' 8" wide and 3' 6" deep, and the floor

of chamber II is 15" above that of chamber I. For a long time I had

considered oil firing, either by carburation or drip-feed. But, when

the time came, I was not well placed to stand the initial cost of an

oil burner and its attendant equipment; and as regards drip-feed, I

had yet to be convinced that this method was sufficiently reliable for

use at high temperature on a workshop scale as opposed to a studio scale

(if I may make a subtle but important distinction). In any case, I had

had a lot of experience with coal and wood firing; and, although the

method is strenuous, used skilfully, it is both cheap and efficient.

There is also a certain romantic element about it. Firings never quite

become routine, which is a good thing in creative craft pottery. It

is also exciting. The incandescent fires and flying sparks, the drumming,

beating vibration of the draught through narrow flues when the temperature

gets up; and the occasional "flash-over" by night from the top of the

chimney after a stoke which has been enthusiastic rather than economical.

Such things have real meaning for me and are more than just incidentals.

But, then, I am and always have been a pyromantic! I have many times

lost my eyebrows and forelock with solid fuel kilns, and once even had

myself mildly on fire: but I would not lightly exchange the heat and

toil for the dial reading and knob twiddling of modern "efficient"

methods. One summer night we fired through a violent thunderstorm. The

yard flooded and began to discharge its load into the firing well, threatening

to drown all the fuel. Two assistants managed to keep me bailed out

while, splashing about, I continued to fire. Then all the lights went

out. We were nearing the peak temperature. Down came the rain and straight

up again it went as steam. The whole atmosphere was an inferno of bursts

of flame and sparks, black smoke, steam, the crash of thunder, the crackle

of blazing wood, the cut and flicker of lightning and the roar of hail

on the temporary tin roof. It was a dramatic scene indeed. What a night!

Yet somehow we enjoyed the holocaust and it was a very good firing.

So the firemouths were designed for solid fuel. There are two, side

by side, the better to heat the width of the kiln. The total grate area

is five square feet. Both fires discharge through wide, arched flues

into a transverse throat extending the whole width of chamber, and eight

inches deep. Seven flues of lintel construction lead through the bottom

of the rear wall of chamber I to another transverse flue the width of

chamber II. From this point several flues extend below the floor of

the chamber as a by-pass to the chimney. These gather into two ducts

before entering the stack, each separately dampered. Six flues lead

from the back of chamber II to the chimney and each of these is independently dampered. Thus, whether or not the by-pass is in use, the

fire can be pulled with remarkable effect from one side of the kiln

to the other. This, with the provision for stoking each side of the

kiln independently, makes for flexibility and is capable of nice adjustment.

The by-pass arrangement, which involved a good deal of complex building,

has fully justified itself; for if the firing of chamber I becomes protracted,

chamber II rises beyond the requirements of our biscuit. There is also

provision for side-stoking chamber II with wood when it is wanted for

glaze. I much want to try this out, but it has not yet been convenient

to the general working programme. very As regards materials, in the

very hot spots which also carry a structural load, we have used Morgan

Refractories' MR1 bricks. These, in my experience, are beyond criticism.

The next hottest places, including the fireboxes, were built of Pearson's

Alite D bricks, which are proving very good. The kiln chambers are double-skinned.

The hot faces are 41" thick and made of Pearson's "p" bricks washed

with liquid Peer "M" cement from the same firm. After three years' use,

there is absolutely no sign of "dropper" formation. Between the hot

face and the outer wall is a one inch cavity filled with finely sifted

ash. The outer wall, since it has to contend with the weather, consists

of a 41" thickness of red engineering bricks. These are rejects from

oxidised areas of blue brick kilns. They are vitreous or semi-vitreous,

dark purple red or red in colour, very strong weather resistant. The

chimney, 15' 6" high and 9" thick throughout, tapers towards the top

and is lined with firebrick for two thirds of its height. There is a

large air damper at the base.

There will be a good deal of tongue clicking,

I fancy, from thermal efficiency experts about this form of construction.

We use grade III or IV coal and we have to buy wood, which is not cheap:

yet the cost of fuel per pot for a double firing (i.e., biscuit to 9000C., plus glaze to 1,3000C. average) is rather less

than 23d. The experts are right in principle, of course, but wholesale

use of high temperature insulation bricks would have doubled the cost

of the kiln, which was exactly £150 in materials. Working on our scale,

when the kiln is only fired ten or twelve times a year, it is more convenient

to spend a few shillings more in fuel than to face a large initial expenditure

on expensive insulating materials. Of course the design of the kiln,

the fuel and the skill with which it is used count for a great deal.

Even so, it is a point of view I would recommend to the attention of

prospective kiln builders if they have so far listened only to the economies

of heat utilisation experts.

For our body we have for years used Messrs. Potclays' buff

clay, to which we add 5% grog and 5% fine red sand, both sieved

40s. to dust, making 10% roughage in all. For larger pots we

increase the size of this; and for a darker body add some red clay

as well.

Four glazes are in regular use for standard ware. A celadon,

a rather shiny feldspar, china clay and ash glaze; a plum coloured

khaki and a wood-ash glaze approximating to Miss Pleydell-Bouverie's classic formula. We produce a Tenmoku by double

glazing first in the khaki glaze, then in the wood ash glaze. The

success of this depends upon exactly the right thickness of the top

glaze relative to the lower one. There are some half a dozen other

glazes which are used on individual pots. All the usual stoneware

decorating methods are in use and we do a great deal of double

glazing, often with a combed finger pattern through the first glaze

while still wet.

Basic production is of standard repetition shapes for which

there is a catalogue. I believe that hand potters should face up to

the problem of supplying well made, usable pots at a reasonable

price. In that way they can make a better contribution to society

as a whole. I have always viewed with suspicion the over-"studio"

approach with its undue emphasis on individuality and orignality

- concepts which materialise so often and so sadly as mere novelty.

Moreover, it caters for too shallow a stratum of the community.

Apart from this, repetition production, provided it is not carried

too far, engenders a self discipline in workmanship and a humility

towards clay which I doubt can be acquired in any other manner.

It is also the only way of gaining real insight into form. No potter

who has thrown a shape to the same superficial measurements,

many hundreds of times, over a period of years and has seen that

shape change, either voluntarily or involuntarily, will fail to understand this.

In addition each kiln contains its quota of individual pots,

whose purpose is chiefly to probe fresh ground, or to re-test by

repetition or variation, the validity of accepted ideas. This counterpoint

of repetition and individuality is, I think, a healthy arrangement.

The making of standard ware is prevented from becoming

dull, whilst individual pots are made on a basis of realities and the

discipline and technique implicit in repetition work.

Firings usually take place once in a month or six weeks. The

usual duration is twenty two hours. It used to be less, and we

have done it in sixteen. But the best is not got out of glazes by

hurrying, which, in a reduced firing, often invites other evils such

as bloating. Kiln setting takes two days and saggars are used

throughout, with intermittent wads to allow the flames to percolate.

The use of open shelves, which would increase the setting space

and theoretically, at any rate decrease fuel consumption, is not

a good proposition with coal fired kilns. The pots tend to become

coated with fine cinder and the glazes become discoloured and

opaque unless they are situated right away from flame passages.

The fires are lit about 8 am and a slow smoking is kept up

for about two hours, when some increase is made. An hour later

the fire is gradually spread over the whole area of the bars and

increased, keeping the atmosphere as oxidised as possible, though

this is difficult at low temperature in such a kiln. As soon as the

mean temperature has risen to 1,0000C, the kiln is thoroughly

"washed" in an oxidising atmosphere to burn up any carbonaceous

matter in the clay body and elsewhere. Then reduction proper

begins. Until now the dampers have been wide open. They are

now adjusted to create more pressure in the chamber. As in most

kilns, the maximum pressure occurs at the crown of the chamber

and decreases progressively downwards. If the kiln is to be worked

efficiently and even heating maintained, and particularly if uniform

reduction is to take place, the pressure must be adjusted so

that it is just positive at the lowest level of the setting space:

that is to say when flame and gases will billow lazily out

if a loose brick is removed at the bottom of the chamber. Over

dampering will obstruct draught and unduly prolong firing. Even

so, as the temperature of the kiln rises more and more, the draught

increases and negative pressure may again occur at the bottom of

the kiln, requiring yet more damper to counteract it.

Between ten o'clock and twelve midnight, cones 1A in all parts

of the chamber should have squatted, and when the mean temperature has risen to about 1,1500C (the hottest zone then being

over 1,200 and the coolest about 1,100) it is time to start stoking

with wood. This wood consists of small billets of split pine. We

burn it, however, on a bed of coal, as we find that a pure wood

fire becomes flimsy after a time. Each bed of coal quite shallow

and made up of fist sized lumps lasts for about six wood stokings,

when it is replaced and followed by further baitings of wood.

The kiln atmosphere becomes a rhythmic alternation of reduction

and oxidation as each batch of fuel burns to ember. Care has to

be taken that the oxidising period of each stoking cycle shall not

be so long as to predominate and therefore determine the prevailing

kiln atmosphere.

It is from 1,1000C to rather over 1,200 that this kiln

seems to progress most slowly: but the slowness is more apparent

than real. For one thing, we have no cones in the kiln to register

any intermediate temperature, so that for a long time there is

nothing to indicate material progress. For another, by this time

fatigue is beginning to set in, and with it impatience. Because of

this and enervation due to the heat, the whole performance seems

to drag, and it is quite likely that a form of boredom may overtake

the stoker. It must be sternly resisted, else the sense of continuity

of what is going on inside the kiln will be lost. One cannot operate

this sort of kiln by rule: only by feel, which is to say by merging

oneself, as it were, with the fire and the materials of the pots. This

may sound esoteric but is pretty near the truth. But for all the

apparent delay, we have not experienced any definite or persistent

sticking, as was sometimes the case at the old pottery. There we

had to keep a stock of what came to be known as "crisis wood."

This was carefully selected pine, absolutely dry and full of resin,

set apart for use only in quite desperate circumstances.

The fall of cone 6A can be expected about three hours after

the fall of cone 1A. Above about 1,2300C, the kiln has a

tendency to accelerate without any change in the method of stoking. Great restraint is now called for. When one is very tired the

temptation to rush the summit is great; but to do so invites flashed

glazes, and it as well to take two more hours to the fall of cone 8.

When cone 9 is down at the top of the chamber, the rhythm of

stoking is changed. A frequent light application of wood is kept

up, with the firedoors open, to create an oxidising atmosphere.

By now, if not before, chamber II will have reached biscuit temperature and is cut out. This atmosphere is maintained for about an

hour, to allow the glazes to settle and the unglazed parts to assume

a warm brown colour. Curiously, there is much confusion about

the kind of atmosphere which produces this colour. It has been

written that it is due to oxidation; again, that reduction is the cause.

Actually, it is a combination of both a long period of reduction

followed by oxidation. The former brings the iron oxide in the

body to a metallic state, making it fuse and concentrate to some

extent on the surface. The subsequent oxidation restores the oxide

in greater concentration and with more colour. A similar body

given a strictly oxidised firing throughout will not acquire this

colour; while a completely reduced firing, in which no oxygen, or

very little, is allowed to enter the kiln after finishing, will leave

the body grey.

There is a small additional increase of heat during this stage,

until the final temperature in the hottest zone is about 1,3500C and in the coolest 1,2500C. This disparity, which the kiln

was designed to provide, exactly fits the range of glazes harder

or softer we use. Sometimes we fire a few pots, made with a

semi-fireclay body and covered with rather refractory glazes, to

over 1,4000C at the back of the firemouths.

When the final test rings have been withdrawn and vetted, the

fires are allowed to burn right through. Then all dampers are

closed to allow the kiln to soak under maximum available pressure

for about ten minutes until cooling has obviously set in. At once

both dampers and firemouths are opened wide to allow a continuous blast of cold air to sweep through, and the kiln is allowed

to cool at high speed through about 4000C. This takes

perhaps an hour and a half. Then dampers and firemouths are

closed and the large air damper in the chimney base is opened to

prevent any pull through the kiln. The firemouths are covered

with bricks and lightly clammed up: but we make no fuss about

sealing all fine cracks. I am not advocating such apparently casual

behaviour as a general rule. It is just that, in our particular

circumstances, it has proved unnecessary. Subsequent cooling

takes only thirty six to forty hours as against three days otherwise.

This is an advantage to one who, like myself, can never get at the

drawing of a kiln fast enough; but the real reason for fast initial

cooling is that it tends to eliminate body-glaze tensions, from

which, at one time, we had a good deal of trouble in the form of

shattering and spiral cracking. Evils of this nature, from which

many stoneware potters have suffered at one time or another, are

usually aggravated by the use of high-silica-content bodies.

The biscuit chamber is allowed to get quite cold before it is

disturbed. At one time we had an unacceptable proportion of fine

hair cracks in the biscuit, particularly in large pots. Very slow

cooling failed to remove the trouble entirely. Now we fire chamber

II to fully 9000C, to allow better sintering, and this has quite

cured the trouble.

Cleaning up, pricing and sorting take about two days. We

supply a number of retailers spread fairly evenly over the country.

About a fifth of the output is sold in our shop on the premises,

and we send to about half a dozen exhibitions a year, selling outright and taking orders. It seems best to get one's eggs into as

many baskets as possible. We have several times turned down

offers which, temporarily, would have been very remunerative,

because their acceptance would seriously have curtailed normal

work and probably would have lost us more lasting contacts.

We have had a fluctuating population at the pottery. My

wife, who helps whenever two small daughters and a rather large

garden permit, makes all our press moulded pots. Various assistants and students have worked here and, I think, have learned a

good deal during their stay. We are grateful for the help they

have given. Nevertheless, I have, for long periods run the pottery

unaided, and I cannot agree with Miss Helen Pincombe that one

alone cannot run standard lines in tableware. We have averaged

five to six thousand pots a year, which does not seem bad considering the large amount of work that has to be done besides the actual

making. It has meant hard work - when single handed about

seventy hours a week and sometimes one naturally gets fatigued.

But it is not work which makes a man tired so much as the attitude

of mind he adopts towards it; and herein lies much of the significance of a craft as a "way of life."

There are no frills in this workshop, and students who come.

here find (I think to their considerable advantage) that they have

to make do with very simple equipment. We use kick wheels. I

would have a power wheel only if I felt it would be justified. We

have no clay making machinery. A pug mill would save labour

but not much time, and so would not pay its way. However, such

austerity, provided it is not taken too far, is wholly good in a craft

such as ours, wherein simplicity and directness of approach have

a value not easily recognised and assessed until much experience

has been gained.

Of materials, we try to keep to very few. To have few, to

know them really well and fully understand their capabilities brings

breadth to one's work. Too many extras tend to cloud the issues

and so have the opposite effect. One cannot hope to gain fluent

mastery of all the possibilities in a wide variety of materials. Better

stick to a few which work and really know them. Similarly with

decoration. Although we have a variety of ways, I always feel

happiest when I can exploit what the interaction of body, glaze

and fire will produce naturally encouraged and heightened sometimes by fluting, engraving or the judicious cutting of facets on the

pot. There is nothing new about this, of course, but it seems to

me to be the best way of working in stoneware.

I hope eventually to build up a three or four man permanent

team. Anything larger, it seems to me, would bring in its train

problems of all sorts, and reduce the leader from a potter to a

mere business manager. But the right personalities are very rare.

In most whom one meets the fire does not really burn. Although

we have never descended to the expedient of making only what we

can sell, our turnover has increased steadily - if slowly - from the

start; but we are now facing greater overheads, and it is not easy,

without capital resources, to plunge into a regular weekly wage bill.

That would require a quick and lasting leap in sales, and I do not

need to tell other potters that this is difficult to arrange. For all

that, I am an optimist about our future as useful members of

society. But we must cater for that society in depth. I feel little

sympathy for the potter sculptor for that is what he really is - in

his studio. Make a proportion of individual, expensive pieces if

you like; but the main effort should be directed towards bringing

the delights of good, hand made pots within the reach of all. To

that end this workshop will unceasingly strive.

Avoncroft Pottery plan

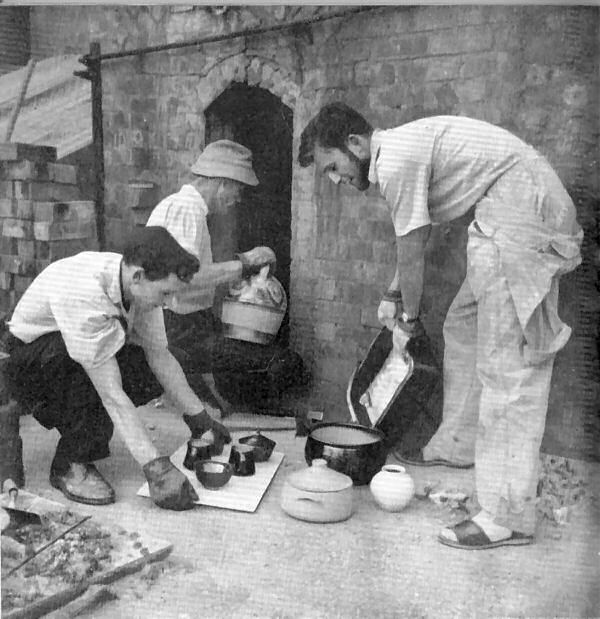

Unpacking the kiln at Avoncroft Pottery in 1958.

Geoffrey Whiting at the kiln entrance with Alan Gayden and and Michael Bailey.

Avoncroft Pottery advert, Pottery Quarterly, Autumn 1955.

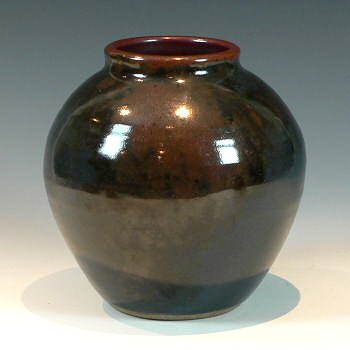

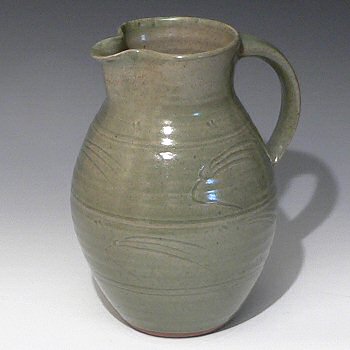

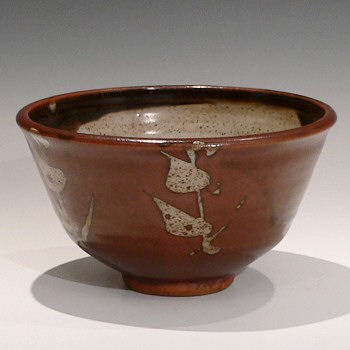

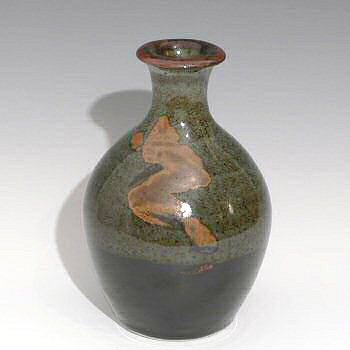

Geoffrey Whiting Pots

Teapot, 13cm tall

Wax resist charger, 31cm diameter

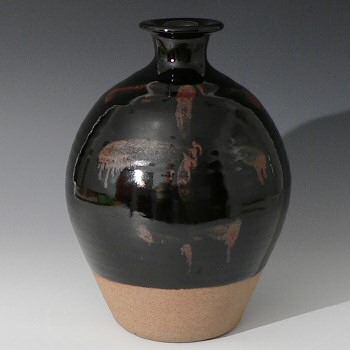

Large bottle vase, 32cm tall

Brush pot, 6cm tall

Fluted bottle, 17cm tall

Globular vase, 19cm tall

Large jug, 27cm tall

Wax resist bowl, 19cm diameter

Teabowl, 7.5cm tall

Teabowl, 8cm tall

Teabowl, 7cm tall

Fruit bowl, Z pattern, 26cm diameter

Vase, 21cm tall

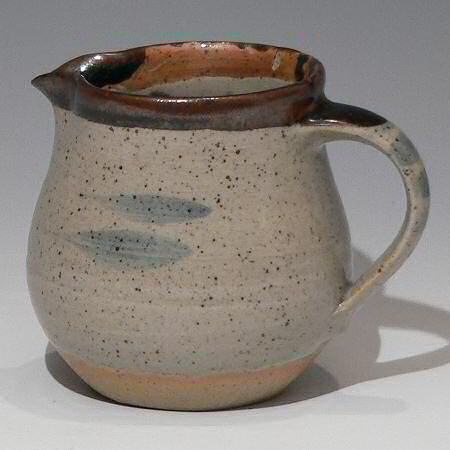

Standard ware cream jug, 11cm tall