Recently I came across an original street photograph of a crowd of people including Bernard Leach, from memory I think David Leach gave it to me when I visited him many years ago.

The image has appeared in Emmanuel Cooper's biography of Bernard Leach and also in Marion Whybrow's book on the Leach Pottery but I thought I would do a high resolution scan and give you the chance to see more detail.

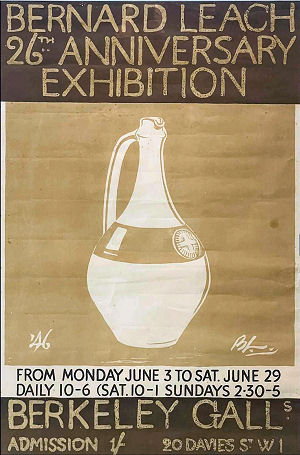

The Berkeley Galleries was a prestigeous venue in London's Mayfair. Opened by William Ohly in 1942 the galleries concentrated on African and Oceanic artefacts and were open until 1977.

After the Second World War when the Leach Pottery had returned to full production Ohly invited Bernard Leach to hold his first postwar exhibition at the galleries in 1946.

The Bernard Leach 26th Anniversary Exhibition ran from June 3rd to June 29th 1946, marking 26 years of the Leach Pottery in St. Ives.

22 packing cases containing 500 pieces of standard ware, tiles and individual pots plus 30 Bernard Leach drawings were sent up to London by the Leach Pottery.

The exhibition invitation card stated that Bernard Leach would give an introductory talk on the situation facing craftsmen, especially potters, at the end of the war and that he would be present at the galleries

during the first week of the exhibition.

An illustrated booklet commemorating 26 years of the Leach Pottery was available priced at 2/6d (12½p). It included this historical essay :

It is twenty-six years since Hamada and I mixed the mortar for the

brickwork of the first St. Ives kiln, clumsily trying to use the long-handled

Cornish shovel to the kindly amusement of the builders who

were completing the roof over our heads.

Where is Hamada now? He and all those other fellow-craftsmen in

Japan with their love of beauty and truth? There is still a curtain of

silence I do not know. No better humans exist on earth, as I assert

from long and varied experience, and none more naturally bent towards

creative peace - the bitter irony of war!

When we started in Cornwall with the helpful understanding of my

partner Mrs. Horne, who a year or two earlier had founded the St. Ives

Handicraft Guild, we neither of us had any experience or knowledge of

crafts in England. Our ideas were more or less bounded by conditions

of craftsmanship in Japan, whether of the traditional countryside, or of the

individual art trained variety, which it so happened that I as a foreigner

inaugurated.

There were highly trained craftsmen in Japan - some of them even

attached to the Court, but not one was aesthetically conscious in the

international and contemporary sense. Thus when they, and still more

the peasant weavers, lacquerers, potters, etc., attempted to graft foreign

ideas onto an already weakened national stem, the results were disastrous.

This is not so much an insistence upon intellectual information and

self-consciousness as essentials to the production of fine living crafts, for

that claim would be easy to demolish with historic example, as a realization

that all over the world the arts of pre-industrial man - the distilled

virtue of milleniums are being destroyed, almost over night, for lack

of breadth of vision.

The conclusion we subsequently came to was that making and planning

round the individuality of the artist was a necessary step in the evolution

of the crafts. So at St. Ives, at the outset, we based our economics on the

studio and not on the country workshop or the factory.

Hamada and I regarded ourselves as being on the same basis as Murray

in London, Decoeur in Paris and Tomimoto in Japan.

For some years our main revenue came from enthusiasts and collectors

in London and Tokyo. We worked hard, but with the irregularity of

mood. We destroyed pots, as artists do paintings and drawings, when

they exhibited shortcomings to our own eyes (what Hamada called

"tail"). We only turned out 2,000 to 3,000 pots a year between four or

five of us and of these not more than 10 per cent. passed muster for shows.

Kiln losses in those days were high - quite 20 per cent.The best pots

had to be fairly expensive. What was left over was either sold here or

went out on that usually unsatisfactory arrangement of "sale and return"

to Craft Shops up and down the country. Nevertheless our work became

known, students arrived, critics were kind, my Japanese friends held

repeated exhibitions of my pots and drawings and sent all the proceeds

to help establish this pottery in my own country. Neither Hamada nor

I, nor Edmund Skinner our first Secretary, ever took more than £100

a year and George Dunn, our clay-worker and wood-cutter, to within

a year of his death was easily the best paid at unskilled rates. Without

private funds, however, and help from Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst

we would not have reached security. Strange as it may seem that only

came with the close of the war.

In 1920 Hamada was 28, I think, and I was 33; he had not yet exhibited

whilst I had been launched in his country as an artist and as a

potter for ten years. He had had a scientific training whilst I had made

a lot of mistakes and gained thereby some experience. Like his own pots

he was well ballasted. For three years we had a good partnership. The

background of thought which we brought to the undertaking was that

of the artist turned craftsman; or at least of the educated and thinking

man perceiving the largely unconscious beauty of material, workmanship

and general approach which preceded the industrial revolution, and his

desire to recapture some of the lost values through the work of his own

hands. So it was with Morris, Gimson and Edward Johnston. East or

West this is the counter-revolution, the refusal of the slavery of the machine.

Both movements started here in England - the return wave of artist-craftsmanship

from Japan has a character of its own - it gained richness,

a reflection of other and different philosophy and culture. Behind the

failure of arms, competition and politics, the world shrinks towards unity

and cohesion.

In 1922 we were joined by the late T. Matsubayashi, engineer, chemist

and craftsman-potter of the 39th generation of a well-known family of

potters. He it was who designed and rebuilt our present, traditional,

three-chambered, down draught "climbing kiln". Hamada returned in

1923 and Matsubayashi in the following year.

At this early stage we were making a lot of rather uneconomic experiments

in the Japanese low temperature faience called "Raku", in middle

temperature English slip-ware and in high temperature, Oriental stoneware

and hard porcelain. The Raku technique was used for Thursday

afternoon demonstrations during summer months at which we allowed

visitors to paint their own pots which we glazed and fired before their

eyes. We were still using wood, and there were not a few occasions when

the beginner's struggle with the unforseen, without the experience and

advice of old hands, made me realise the truth behind the friendly warning

that in Japan 20 years were regarded as about the time requisite for the

establishment of a new pottery. There was one firing about 1924 which

lasted twice as long as usual - 72 hours. I had two hours off during that

time and could hardly stand up at the end. The fire-bars below the mass

of white-hot ember became choked with a treacly mass of mixed ash

and a flux from salt with which, unknown to us, some of the wood had

been saturated. Eventually, raking desparately at the fire-mouth I drew

out long streamers of slag-glass and freed the air passages once more and

the temperature soared.

About this date Mr. and Mrs. Elmhirst came to see me and made the

suggestion that we should transfer the pottery to Dartington Hall, near

Totnes, where they had bought a great medieaval estate and were starting

a progressive school and round it a community engaged in rural crafts.

At that time I did not see my way to uproot here and I suggested, as an

alternative, Sylvia Fox-Strangways, who had been at the pottery a short

time.

Between 1920 and 1931 we had "one-man" shows, first at the Cotswold

Gallery in Soho, then at Patterson's Gallery, Old Bond Street, then at the

Beaux Arts in Bruton Street. About seven altogether. They were moderately

successfull, but it became gradually clear to me that the solution

to the underlying problems of craftsmanship, or at any rate those which

presented themselves to my mind most forcibly, were not likely to be

discovered in the expensive precincts of Bond Street - that springboard of

virtuoso and showman.

So we made an experiment in Church Street, at the "Three Shields",

and again as a group of our own at the New Handworkers' Gallery in

Bloomsbury. From there we published a small series of craft pamphlets

printed by Pepler at the St. Dominics Press, Ditchling. Mine "A

Potter's Outlook" - was my first attempt in England to formulate faith

and ideas. That was in 1928.

Meanwhile our pots had been shown at various national and international

exhibitions, Wembley, Paris, Milan, Leipsic, etc. At the invitation

of a group of students of Harvard University I joined with Murray,

Cardew, Bouverie and Braden in a combined Anglo-Japanese individual

potter's exhibition. It was spoiled, however, by delays and by rough

handling in the Customs, but I think it worthy of mention because of the

newness and breadth of the idea.

When the remnants of this show went to Japan, rather hidden amongst

the bouquets, I found one penetrating, disconcerting, criticism: "We

admire your stoneware (in the Oriental mode) but we love your English

Slip-ware - born not made." That sank home, and together with the

growing conviction that pots must be made in answer to outward as well as

inward need, determined us to counterbalance the exhibition of expensive

personal pottery by a basic production of what we called domestic ware.

Student apprentices followed one another at intervals of about a year

apiece. After Michael Cardew, Katharine Pleydell Bouverie, then Norah

Braden, most sensitive of all who have worked here. They combined

and made fine pots at Coleshill. Muriel Bell who set up at Malvern;

William Worrall and John Coney who ran a kiln together behind Glastonbury

Tor, until Worrall's premature death in 1940. Charlotte Epton,

Barbara Millard who was thrown from a horse and killed in South Africa,

and about a dozen other preceding the war. In 1930 my eldest son,

David, decided against University and for a potter's life. My second son,

Michael, also worked with me for a time.

Besides long-term apprenticeship, which is the only real way of learning

a craft, we did have short courses which more than 100 must have attended

at one time or another a few repeatedly, such as Kenneth Murray who

has had much to do with native crafts in Nigeria.

Plain and decorated stoneware tiles were developed from 1930 onward.

The quiet variations in broken colours yielded by open firing at high

temperatures are admirably suited to this purpose, and of course the

tiles themselves are very durable. Later experience has led to the

conclusion that the scale of production would have to be greater to bring

adequate profits, and that much of the work is only suitable for mechanical

reproduction. Experiments have been our danger, we have made enough

to start a dozen potteries each on different lines. During the six years

preceding the war we exhibited at Muriel Rose's delightful "Little

Gallery" off Sloane St. together with our English and Japanese craftsmen

friends.

In 1933 I went to teach, part-time, at Dartington School, leaving

David in charge for a month or two at a time. The Elmhirsts built a

small pottery unit for me at Shinner's Bridge in which I developed the

English slip-ware technique, using the chocolate-coloured Fremington

clay from North Devon, which is the same as that used at Lake's Pottery,

Truro, the last of the traditional Cornish kilns. But I vitrified the body

by taking the temperature to over 1000°C. and used an excellent black

engobe or slip - often trailing white over black and dipping into transparent iron glaze

so that the effect was yellow on shot black.

Life at Dartington was enriched with personal and artistic contacts

and the intermingling of nationalities: Joos Ballet, Tchehov drama, music

under Hans Oppenheim, drawing, painting, sculpture and exhibitions

of living art.

My closest friend was the American artist Mark Tobey with whom I

travelled to the Far East in 1934. My old companions of art in Japan,

particularly those associated with what had become a national craft

movement, had invited me to revisit them and work in their several

centres for a year. Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst felt that such an

invitation should not be refused and they not only financed me but also

Mark, who accompanied me to Shanghai, and whom I met again for

a short time in Tokyo. This is no place in which to attempt to describe

the happenings of that amazing year. As far as work was concerned it

was the fullest in my life and humanly in sharpest possible contrast to

the terrible apparition of Japan which war has brought to the mind of

the West. With Hamada in Mashiko, Tomimoto in Tokyo, Kawai in

Kyoto, and Funaki in Matsue, and in three other potteries, the pots and

drawings were done for eleven exhibitions. Besides that, with Yanagi as

leader, we travelled 4,000 miles collecting examples of folk art, planning,

lecturing, criticising. This work was rewarded by the promise of adequate

funds for the building and maintenance of a beautiful National Museum

of "people's art", which I desparately hope was not destroyed by Allied

bombers.

Whilst I was in the East David was sent to Stoke Technical College

for a two-year Course (Bernard Forrester went to Dartington to teach),

and St. Ives was left in charge of Laurie Cookes and Harry Davis, who

carried on the production of domestic slip-ware with great energy.

Samples were taken by car far afield, personal contacts made and the

orders were carried out forthwith, involving sometimes half a dozen

kiln-firings without a break.

Some time after I got back I decided to leave David in charge once

more. Laurie and I bought a car and caravan in which we lived for a time

at Ditchling, then at Winchcombe near Michael Cardew, and finally at

Dartington. There I began to write "A Potter's Book" for Richard de

la Mare of Fabers. At the same time I resumed potting and a little

teaching of adults besides making periodic visits to St. Ives where David

was making a number of technical improvements, including the successful

installation of an oil-burner and air-blower in 1937. Then we gave up

slip-ware in favour of stoneware because it suits the conditions of modern

life better and offers a wider field of suggestion and experiment.

Dear old George Dunn died in 1940, but his son Horatio had taken

over the job in 1937. The following year we engaged our first two local

apprentice lads.

In 1940 my book was published. Despite the war it has sold well, both

here and in the U.S.A., and it has brought me friends and contacts with

potters far and near. The first edition was curtailed by bombing, but

a second has appeared and has been twice re-printed.

Late in 1940 I made St. Ives my headquarters once more in response

to my son's appeal. Not only did he anticipate his "call up", but he was

also feeling at a loss in interpreting my shapes and patterns at a distance

of a hundred miles. By this time we had issued our first catalogue of

domestic stoneware and ovenware as well as a tile catalogue.

One night in January 1941 the pottery had the bad luck to get in the

way of a parachuted land-mine intended for the nearest air-field, ten miles

away. It fell in the garden, blew down George Dunn's old cottage and

shook or sucked off slate roofs, glass, doors, etc., and broke pots, etc., to

the tune of £2,000. Personal injury was light - what to do next was the

problem. With difficulty we hired canvas to cover the pottery proper,

but the house was condemned by St. Ives, Plymouth and Bristol (three

times). Not only that, but we were blamed for the happening by the

local people, and we were not permitted to explain in the press that the

pottery had not been signalling to German planes by kiln-fires. (They

had been unused for two months!) Eventually our Member of Parliament

took the case up and it was fairly and sympathetically reviewed by

the Board of Trade, after three years' uncertainty. Repairs were thorough

and we were even granted a Special Licence to make and sell outside

"Utility" regulations, and to employ seven workers-if we could find

them We did twelve in all at different times-but only two or three

partially trained, so production lagged.

We were granted David's release 6 months ago, old hands are returning

and new ones want to come in unprecedented numbers. We are fortunate,

but the war hit British Craftsmanship hard. Out of the 2,000 or so craftsmen

of peace time (excluding rural crafts) there were fewer than 20

workshops left. The thread of continuity upon which traditions of right

making depend has worn very thin during these six years.

Crafts such as pottery depend, as it were, upon a slow passage of time:

the gradual transfer of the bodily knowledge of the right usage of material

and the intimate co-operation of small groups of workers. Break those

threads and disperse the men and their tools, and an heritage is lost for

ever. This is one of the contingent tragedies of total war and it is the

more poignant because craftsmanship in its essence is the antidote of

mass-production and the craftsman is the residual type of fully responsible

workman.

This responsibility comes to its maturity with conscious knowledge.

At that stage the artist-craftsman can inaugurate experiments in group

craftsmanship such as ours at St. Ives.

We have aimed at a high common denominator of belief and in the

sharing of responsibility and profits. By accepting the Cornish motto

"one and all", and by making the workshop a "we job" instead of an

"I job" we appear to have solved our main economic problem as handworkers

in a machine age and to have found out that it is still possible for

a varied group of people to find and give real satisfaction because they

believe in their work and in each other.

To me the most surprising part of the experience, which now covers

about ten years, is the realization that - given a reasonable degree of

unselfishness, divergence of aesthetic judgment has not wrecked this

effort. When it comes to the appraisal of various attempts to put a handle

on a jug, for example, right in line and volume and apt for purpose,

unity of common assent is far less difficult to obtain than might have been

expected.

During the war representatives of the two principal craft societies

constantly met to investigate, and argue, and to supplicate the government

through the Joint Committee of the Central Institute of Art and

Design, under the chairmanship of Sir Charles Tennyson.

Through it some relief has been granted in individual cases and a

modicum of raw materials released, but so far we have not been able to

obtain any recognition of the function of craftsmanship in the social order,

nor any general protection from regulations governing industry, which are

crippling to craftsmen. Even now it is exceedingly difficult to obtain

licences to make and sell crafts. The craftsman's contribution to national

life requires the protection of the Government: without it, the continued

existence of free craftsmanship, with all its implications, is at stake.

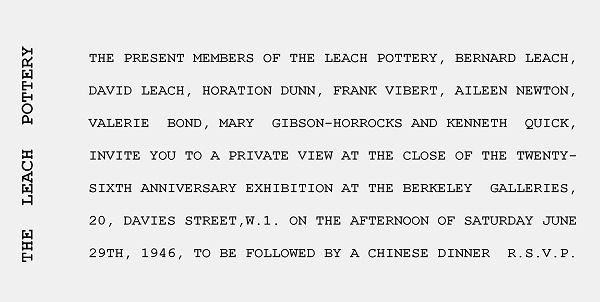

At the end of the exhibition David Leach took a group photograph before the invitees were treated to lunch at a Soho Chinese restaurant. The St. Ives printer Guido Morris designed the invitation card for the celebratory meal, it was printed in capitals and read ...

As this second private view was at the end of the exhibition Mr Ohly will have decreed that the exhibition to remain intact with purchases being collected after closure.

Group photo outside the Berkeley Galleries at the closure of the Bernard Leach 26th Anniversary Exhibition, June 1946

The site of the Berkeley Galleries now, via Google Streetview

References:

| Emmanuel Cooper | Bernard Leach: Life and Work, Yale, 2003 |

| Marion Whybrow | Leach Pottery St. Ives The Legacy of Bernard Leach, Imago, 2006 |